The Early Paleozoic Era

Animals first appeared in ancient seas about 600 million years ago. Over the following several hundred million years animal groups diversified and went extinct in response to major global changes in climate, sea level, and mountain building. Learn about diversification of marine animal life below.

The Cambrian: Evolution’s “Big Bang”

At the beginning of the Cambrian, all of the basic kinds of animals, or phyla, appeared abruptly, within a 10-20 million year “blink of an eye” in the fossil record. This is one of the most important events since the origin of life more than 3 billion years earlier. Scientists call it the Cambrian Explosion.

The groups of animals that appeared in the Cambrian Explosion continued to play out life’s drama for the next 545 million years.

Why did it happen?

The Cambrian Explosion is one of the greatest mysteries in the history of life and the subject of intense research. There are two basic ideas:

Genetic innovation: Something inside the genetic make-up of organisms may have changed, leading to greater variability.

Environmental change: Stresses in the environment—perhaps stemming from glaciation—may have accelerated evolution by intensifying natural selection.

The answer may involve both.

First Indications of the Cambrian Explosion

Trace Fossils

Not all fossils are bones or shells. Sometimes the tracks or traces of an organism are preserved too. Geologists recognize the beginning of the Cambrian period by the first appearance of a particular type of trace fossil called Treptichnus pedum. Trace fossils became common during the Cambrian Explosion.

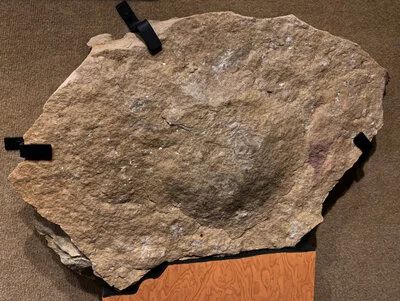

Mollusk (?) trackway, Climactichnites wilsoni, from the Late Cambrian of Blackberry Hill, Wisconsin (PRI 57023).

The tire-like tracks shown in the fossil Climactichnites wilsoni were probably formed by large, slug-like mollusks crawling across an ancient tidal flat. How do we know? The shapes of these ancient tracks resemble tracks made by some snails today. Nearly 500 million years ago, these tracks represent one of the earliest records of life very close to the seashore, perhaps on tidal flats.

Small Shellies

The first mineralized hard parts preserved in the fossil record consist of a puzzling assemblage of tiny skeletal pieces known as “small shellies.” Exactly what these animals were is not completely known, but they might represent bits and pieces of larger animals.

Scanning electron micrographs of “small shellies” from the limestone at Claverack, New York.

Sea Life Sorts Itself Out

Even though nearly all of the larger animal groups (phyla) originated in the Cambrian Explosion, overall diversity in the Cambrian fossil record is relatively low. Trilobites (see Fossil Focus below) were the dominant group of organisms in the seas, but sponge-like archaeocyathids, jellyfish (see Fossil Focus below), and certain brachiopods were also common.

The corals, brachiopods, and crinoids that dominate the rest of the Paleozoic had only a minor presence in Cambrian oceans, and little or no life was on land.

Fossil Focus: Trilobites

Trilobites. Paradoxides harlani from the Early Cambrian of Norfolk County, Massachusetts (PRI 50233).

Trilobites are arthropods—invertebrate animals like today’s insects, crabs, and spiders. They inhabited ancient seas across the world, crawling along or swimming above the seafloor as predators, scavengers, or filter feeders. They were highly diverse and over 20,000 species are known—some small, some large; some smooth, some spiny. They reached their maximum diversity during the Cambrian period and survived for nearly 300 million years (until the end of the Permian period); that’s 1500 times longer than modern humans have existed.

Fossil Focus: Jellyfish

Fossil medusoid (jellyfish). Hippolytus cynthia from the Late Cambrian of Marathon County, Wisconsin (PRI 64789).

Because their bodies are made of soft tissues, and have no shells, bones, or other hard parts, jellyfish are extremely rare in the fossil record. This specimen, however, is one of hundreds discovered in an area called Blackberry Hill, in central Wisconsin. So how is something as delicate as a jellyfish fossilized?

Long ago, a jellyfish was stranded on a sand flat. In an attempt to escape, it pulsed its body upwards, shaping the sand underneath into a dome. The jellyfish died and was quickly buried. Sticky mats of microbes, like bacteria and algae, held the sand and the jellyfish together long enough that they could be preserved. As fossilized remains of jellyfish are so rare, this is a spectacular example of what paleontologists call “Exceptional Preservation.”

Windows into the Cambrian Explosion

Much of our understanding of the true scope of the Cambrian Explosion—beyond the mineralized hard parts of common Cambrian fossils like trilobites and brachiopods—is based on a small number of fossil localities positioned in time just before and after the event. These localities are important because they preserve evidence of completely soft-bodied organisms that typically have no chance of becoming fossils. They are critical windows into the events of the Cambrian Explosion.

Window 1: The Ediacara

Ediacaran fossils. Top: The jellyfish Madigania annulata from the Ediacaran Period of Ediacara, South Australia (PRI 49848). Bottom: An artificial cast of the seapen Charnia masoni from the Ediacaran Period of Leicestershire, England (PRI 49767).

The Ediacara fossils are the oldest multicellular organisms known from the fossil record. First found in 1946 in the Ediacara Hills in South Australia, these soft-bodied organisms were preserved in sandstone that formed on the seafloor about 600-545 million years ago—before the Cambrian Explosion!

What were the Ediacara organisms? Some Ediacara fossils were probably ancestors of later kinds of animals, such as jellyfish, soft corals, or worms. Others may have been outside the main evolutionary lines, representing failed evolutionary “experiments” that left no descendants.

Window 2: The Burgess Shale, British Columbia

The Burgess Shale is a rock formation in the Canadian Rockies, British Columbia, that formed approximately 505 million years ago—only 40 million years after the start of the Cambrian Explosion. Fossils in the Burgess Shale show that tremendous diversity had already evolved in the Middle Cambrian

Burgess Shale fossils are famous for their extraordinary preservation. They show soft-bodied animals, and the soft parts of hard-bodied animals, that were buried by an underwater avalanche of fine mud. More than 100 different species have since been found in the Burgess Shale since it was discovered in 1911.

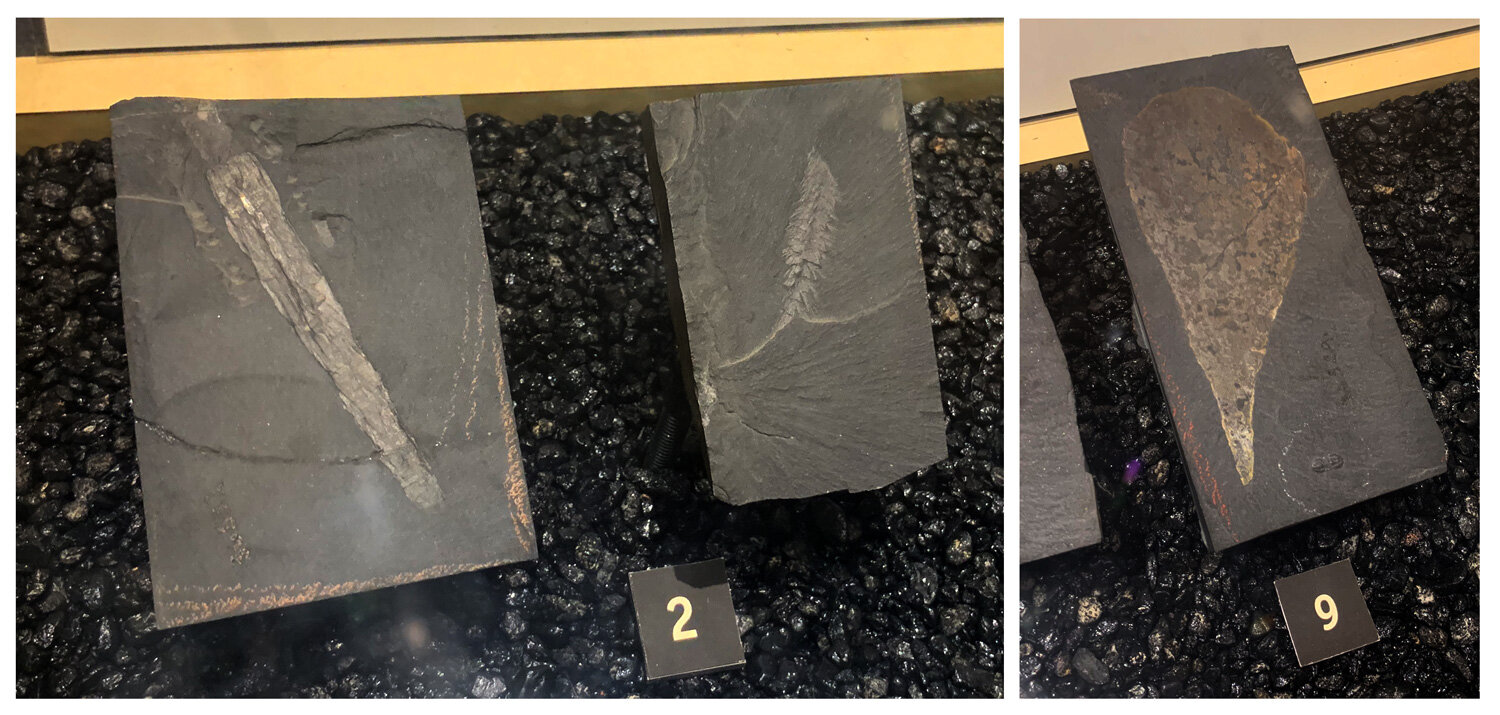

Fossils from the Burgess Shale, Burgess Pass, British Columbia. Left: The priapulid worm Selkirkia major (PRI 50286). Middle: The arthropod Canadia spinosa (PRI 50288). Right: Headshield of the anomalocaridid Hurdia victoria (PRI 50605).

Window 3: Chengjiang, China

Fossils of the Chengjiang Fauna are similar to and just as magnificently preserved as those of the Burgess Shale, but older—from the Early Cambrian! They were first found in 1984 in the Yunnan Province of China.

The rocks containing Chengjiang fossils formed around 525 million years ago—only about 20 million years after the start of the Cambrian Explosion.

The Chengjiang fossils help pinpoint the time of the Cambrian Explosion—telling us that the amazing diversity of life in the Burgess Shale appeared more abruptly than previously thought.

Behind the Glass & In the Drawers: Cambrian Fossils

The Digital Atlas of Ancient Life project at PRI has created interactive 3D models of some of the Cambrian-aged specimens on display at the Museum of the Earth and stored “behind the scenes” in the PRI Research Collection. Explore the models by clicking on the triangle in the middle of the image; they may be rotated and zoomed in on using your mouse.

Archaeocyathids

A group of sponges that are only known from the Cambrian fossil record. Learn more about archaeocyathids on the Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life.

Fossil specimen of an archaeocyathid from the Lower Cambrian. Specimen is from the teaching collections of the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI T-229).

Trilobites

Trilobites reached their maximum diversity during the Cambrian period.

Fossil specimen of the trilobite Wanneria walcottana from the Cambrian Kinzers Formation of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (PRI 76846). Specimen is from the research collections of the Paleontological Research Institution. Trilobite is approximately 12.5 cm in length.

Fossil specimens of the trilobite Elrathia kingii from the Cambrian Wheeler Formation of Millard County, Utah (PRI 76837). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution. Length of larger specimen is about 4 cm; length of smaller specimen is about 3 cm.

Inarticulate Brachiopods

Inarticulate brachiopods are common fossils in Cambrian-aged rocks; many have the shape of a fingernail. Learn more about brachiopods on the Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life.

External mold of the fossil brachiopod specimen Wimanella simplex from the Cambrian of British Columbia, Canada (PRI 38668). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 2 cm.

Specimens of the inarticulate brachiopod Obolus matinalis from the Cambrian of Polk County, Wisconsin (PRI 76740). Specimens are from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 7 cm.

Eocrinoid (Echinoderm)

Eocrinoids are a strange group of echinoderms (the group that includes modern starfish and sea urchins) that are only known from the fossil record of the early Paleozoic.

Fossil eocrinoid Gogia sp. from the Cambrian Spence Shale of Utah. Specimen is on display at the Museum of the Earth. Length of specimen is approximately 8 cm.