Devonian Geology

Top: Geologic map of New York. Bottom left: North-to-south simplified geologic cross section from Oswego to Waverly. Bottom right: Approximate thicknesses of Paleozoic bedrock recorded at the Cornell University Borehole Observatory (CUBO). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks and the Paleontological Research Institution.

Penn Dixie

Hunt for Devonian fossil at Penn Dixie Fossil Park!

Image courtesy of Alasdair Gilfillan.

Penn Dixie Fossil Park & Nature Reserve near Buffalo, New York, lets visitors collect and keep Devonian marine fossils. Run by the Hamburg Natural History Society, Penn Dixie is a nonprofit dedicated to the hands-on study of nature. Rocks in this area are from the Hamilton Group, layers filled with fossils from the middle of the Devonian Period. Penn Dixie is known for its Eldredgeops and Greenops trilobite fossils.

Penn Dixie Fossil Park was originally a quarry for the main rock ingredient used in construction cement. It is named for the quarry’s last owners, the Pennsylvania-Dixie Cement Company. Rock was taken to the shores of Lake Erie, processed into cement, then loaded onto trains and ships. Quarrying ended by 1970 and the site then became known for its fossils. In 1993, the Town of Hamburg purchased and donated the land to the Hamburg Natural History Society. The site was developed for science education and now welcomes 20,000 visitors annually.

Penn Dixie Fossil Park is a wonderful place for beginners and experts to hunt for fossils. The site is only a 2.5 hour drive from Ithaca. Visit Penn Dixie’s website for hours, pricing, and educational activities. To help you with your fossil identifications, consider purchasing a copy of PRI's Field Guide to the Devonian Fossils of New York.

Images courtesy of Penn Dixie.

The rocks and fossils of Penn Dixie

Layers of the Hamilton Group can be found across Upstate New York, including here in Tompkins County. Only the tiniest grains of sediment washed down from mountains, across the Devonian sea, to the place we now call Penn Dixie. The rock layers at Penn Dixie are fine-grained calcareous shales.

The tiny grains of sediment that make up the shale were especially good at preserving fossils. Small creatures like brachiopods and delicate crinoid stems are found all over Penn Dixie. You can also find rare pieces of ancient armored fish and fragments of fossilized plants that washed out to sea.

Devonian fossils collected at Penn Dixie. These specimens were collected and prepared by Alasdair Gilfillan; they are part of his personal collection and are on loan to PRI for the “NY Rocks!” exhibit.

Collector Spotlight

Alasdair Gilfillan’s interest in fossils began at a young age, when visiting the Yorkshire Coast of England with his parents and brother. Apart from being a beautifully quaint old fishing village, it is also world famous for its Lower Jurassic marine fossils, particularly ammonites, belemnites and marine reptiles. After finding an ammonite on the beach, he became addicted to fossil collecting and his passion for hunting for fossils has continued to the present day. About six years ago, Alasdair and his wife visited the Penn Dixie fossil site for the first time. He quickly became hooked and now tries to visit the site at least two or three times a year. Some of the Penn Dixie specimens that he has collected and prepared are highlighted in the photo above.

Identify your Devonian fossil discoveries!

Field Guide to the Devonian Fossils of New York by Karl Wilson.

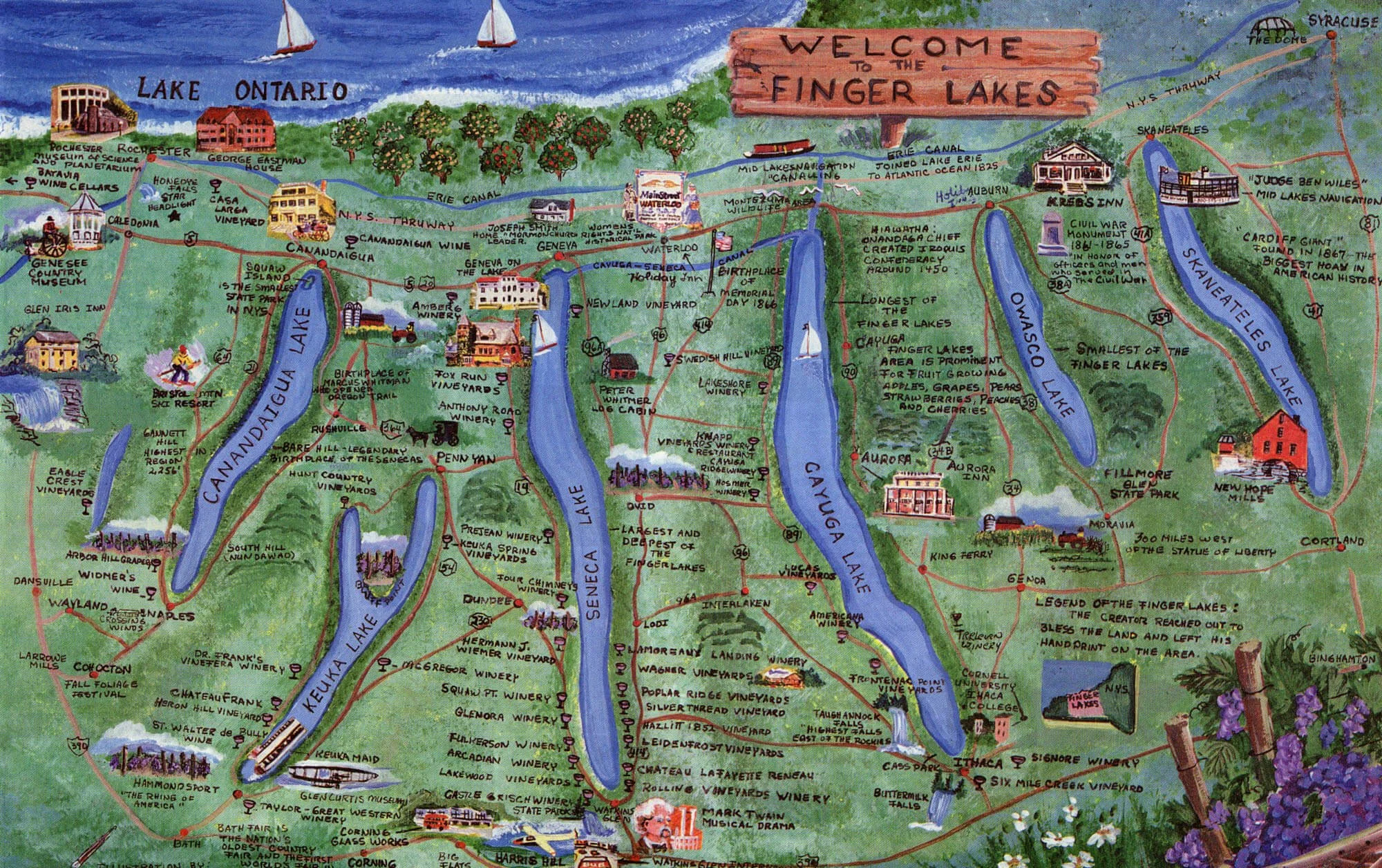

Finger Lakes

Cutting the Layer Cake

Layered Devonian bedrock is revealed in the high walls of gorges, quarries, roadcuts, and streams in the Finger Lakes Region. The rock layers across the 11 Finger Lakes come from the same source: sand, silt, and mud that washed into a shallow sea from the Devonian Acadian Mountains. Rocks in different parts of New York show us different parts of the ancient Devonian environments.

Each gorge also exposes rocks from a slightly different range of geologic time. These rocks, together with other outcrops, tell the story of the ancient mountains and sea. Because of later mountain-building, the layers are slightly tilted toward Pennsylvania and are also at higher elevation in the Southern Tier. Because of this, rocks at the surface in the southern tips of the Finger Lakes are younger than rocks to the north. Most of the rock we see are fine-grained sandstones, siltstones, and shales, but limestone is found in a few places.

Borodino Quarry of Tully, August 1928. Photo courtesy of O.D. Von Englen

Limestone is made mostly from the shells and skeletons of organisms that lived in shallow, clear seawater. Erosion of silt and mud into the sea created an unfavorable environment for limestone-forming animals during most of the Devonian. We do not fully understand how the widespread limestone beds of the Tully Limestone, the only major limestone layer in Central New York, formed during this interval. You can see the Tully Limestone in the creek bed and Lower Falls at Taughannock Falls State Park.

Though there are some layers of Upper Devonian rock in the Southern Tier that have abundant fossils, the layers in the gorges at the southern end of Cayuga and Seneca lakes have few or no fossils in them.

Why is Ithaca Gorges?

Ithaca’s gorges formed long after the Devonian Period, and are still forming today. During the Ice Age, continental glaciers flowed south from Canada, melted back, and advanced again numerous times. These glaciers once covered Upstate New York, smoothing the surface, carving the Finger Lakes, and leaving sediment behind. The gorges later formed as waterfalls flowed into the lakes. The water cut into the streambed, creating channels now known as the gorges.

Development of a hanging valley following glacial retreat. (left) | Development of a post-glacial gorge as seen in the Finger Lakes Region of Central New York. (right)

Taughannock Falls

Taughannock Falls State Park

LOCATION: Southern Cayuga Lake

AGE: Middle through Late Devonian

FORMATIONS: Moscow, Tully, Geneseo, Sherburne, and Ithaca Formations

ROCK TYPES: Limestone, shale, black shale

There are almost no fossils in the Geneseo Formation, but its black color comes from carbon. Dead organisms sank to the sea bottom and didn’t fully decay. Instead, the carbon from their bodies remained in the dense black mud. This only happens in stagnant-water environments, where there isn’t enough oxygen for bacteria that cause decay. At Taughannock, we see a dramatic contrast between clear waters that formed the limestone of the creek bed and the muddy ingredients of black shale above. Because it contains so much carbon, deeply buried layers of black shale are a source of oil and natural gas.

FUN FACT: The contrast in hardness between the limestone and the softer black shale above it led to the distinctive square U-shape of Taughannock Creek gorge.

EXPLORE MORE: Geology of Taughannock Falls State Park on Earth@Home.

Lucifer Falls

Robert H. Treman State Park

LOCATION: South of Cayuga Lake

AGE: Late Devonian

FORMATIONS: Ithaca Formation

ROCK TYPES: shale, siltstone

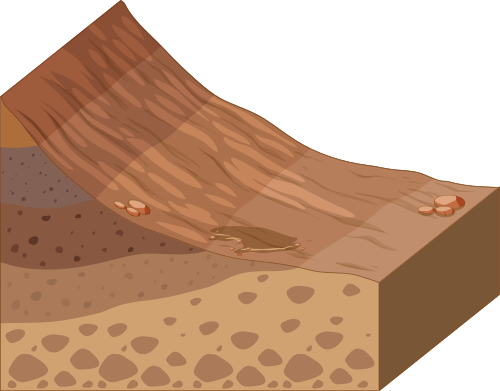

Some rock layers formed from an underwater landslide. Sand and mud suddenly rushed down the sloping seafloor. Larger, heavier sand particles sunk to the bottom first, with finer clay sediment landing on top. Each set of coarse and fine-grained layers is called a turbidite. These alternating layers are visible in the gorge walls.

FUN FACT: The smooth vertical walls at Treman formed where cracks called joints allowed large blocks of rock to fall off the sides of the gorge. These cracks formed when the rock was deep beneath the surface, long after the layers had been deposited, but well before the layers were exposed at the surface.

Cascadilla & Fall Creeks

LOCATION: Northern and southern boundaries of the Cornell campus

AGE: Late Devonian

FORMATIONS: Ithaca Formation

ROCK TYPES: shale, siltstone

A walking trail along Cascadilla Creek runs from Collegetown to the eastern edge of downtown Ithaca. Fossils, especially brachiopods and bivalves, can be found in rocks along the creek.

FUN FACT: Fall Creek was dammed by Ezra Cornell in the early nineteenth century to create Beebe Lake. The dam allowed control of water flow for a mill near Ithaca Falls.

EXPLORE MORE: Geology of Cascadilla Gorge on Earth@Home

Watkins Glen State Park

Watkins Glen State Park

LOCATION: Southern tip of Seneca Lake

AGE: Late Devonian

FORMATIONS: Genesee and Sonyea groups

ROCK TYPES: shale, siltstone

FUN FACT: Compared to Ithaca, Watkins Glen is further away from the ancient Acadian Mountains. The sediments eroding from these mountains had to travel farther across the ancient sea. Only lighter and smaller sediments could be washed that far from their source. The fine grains of Watkins Glen shale and siltstone create less angular shapes when they weather away. The rocks have more rounded edges, fewer straight cracks in the ground, and more “potholes” drilled by swirling water.

Letchworth State Park. Photo courtesy of Bill Hecht.

Letchworth State Park

LOCATION: Southwest of Rochester

AGE: Late Devonian

FORMATIONS: West Hill Formation, Gardeau Formation

ROCK TYPES: shale, siltstone

FUN FACT:

Letchworth Gorge has been called the Grand Canyon of the East. It is outside the Finger Lakes region, but its rocks are roughly the same age as the gorges around Ithaca.

Devonian Quarries and Industry

Quarries and Industry in New York

Quarry in Union Springs, New York in the 19th century.

Photo courtesy of Bill Hecht.

New York’s Devonian rocks are important not only for understanding ancient life on Earth, but also for our lives today. For well over a century, New York’s Devonian siltstone, sandstone, and limestone bedrock has been quarried for building stone and aggregate.

Many of the historic buildings on the Cornell University campus are built from Late Devonian rocks as well as buildings on PRI’s West Hill campus, which includes the Museum of the Earth. A locally-famous type of building stone is “llenroc,” which is “Cornell” spelled backward. This stone comes from a quarry in the Ellis Hollow area of Ithaca. It was used to construct Willard Straight Hall, Myron Taylor Hall, and the Baker Lab on Cornell’s campus (as well as Ezra Cornell’s house, which was named Llenroc). Llenroc can also be seen in the stonework leading up to the second and third tier parking lots here at the Museum of the Earth. The quarry that produces llenroc is still active today and is called “Finger Lakes Stone.”

Rock from the slightly older Ithaca Formation was quarried on Cornell’s campus to construct some of its oldest buildings, including Morrill Hall, White Hall, and McGraw Hall. McGraw Hall served as the first home for Cornell’s geology department (now located in Snee Hall).

Modern buildings rarely use natural rock as a building material. Most local quarries now mine Devonian rocks for aggregate, which is crushed rock that is sorted into different sizes. Aggregate is often used in the construction of roads and parking lots. It is also frequently mixed with the concrete used in construction of buildings, bridges, and other structures.

Many gravel driveways in Upstate New York are also constructed from aggregate from local Devonian rocks, which is why it is frequently possible to find a small fossil in your gravel driveway!

Llenroc House in Ithaca, New York. Construction of Llenroc, built by Ezra Cornell on East Hill, took seven years and was finished in 1874.

Photo courtesy of Bill Hecht.

Finger Lakes Wine and Geology

Finger Lakes Wine Region

New York’s main wine regions are Long Island, the Hudson Valley, and the Finger Lakes. All three have soils with the right mix of acidity, nutrients, and water for grapes to grow. Combined with the right temperatures and changing seasons, these conditions allow over 100 wineries to flourish in the Finger Lakes.

Although minerals and chemicals from the soil do not directly affect the taste of wine, geology contributes to grape agriculture in many other ways. Wine grapes need deep, well-drained soils, moderate temperatures, and neutral soil acidity. Long cracks in the Devonian shale and limestone, called joints, allow grapevines’ long roots to dig deep into the ground. Although the climate in the northeastern United States is usually too harsh for grapes, the Finger Lakes’ sloping shores keep the temperature stable, with warmer winters and cooler summers around the rims of the lakes.

Devonian Bedrock

Our Devonian bedrock consists of alternating layers of limestone, shale, and siltstone. Each kind of rock breaks down into a different soil type. Siltstones and shales produce acidic soils, while limestone, made up of calcium carbonate, can be dissolved by rainwater and balance out the acid. Farmers often add ground limestone to help neutralize the pH of their soils.

The size of soil particles also matters for water supply. Finer-grained soils may hold too much water and become soggy, while larger grains have better drainage but may not be able to hold enough water. Areas that were once ancient deltas of streams flowing into lakes have a variety of large and small soil particles that create balanced growing conditions. Many of the Finger Lakes’ wineries are located at these sites.

Because the Devonian bedrock of the Finger Lakes tilts down toward the south, different rock types can be exposed at the surface over a very small area. Even within a single vineyard or field, drainage and water supply may vary significantly. Ultimately, almost every aspect of how well grapes can grow in the Finger Lakes comes down to geology.

Did you know?

European wine grapes were brought to the U.S. in the seventeenth century, but they didn’t grow well until they were hybridized with native North American grapes.