Strides in Museums, Academia & Research

Barriers in Museums, Higher Education & Research in the Early 1900s

Early in the history of science, scientists could learn from mentors outside the classroom. As technology improved, working in science required more specialized skills and knowledge. By the 1900s, most people needed a university degree, published research, support from peers, and a paid position to succeed. Women pursuing a career in science met resistance at every level.

In the early 1900s, women began to find paid positions in paleontology and geology. Scientific jobs for women were usually low level or limited to teaching at women’s colleges. Employers paid women lower salaries or sometimes did not pay them at all. Many would not employ married women. There were few opportunities for women to earn promotions, and some men refused to work with women. Women of color experienced even more severe discrimination and were often pushed out of the scientific workforce.

Featured Paleontologists

Women in Paleontology At Cornell and PRI

“I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study.”

– Ezra Cornell, Cornell University motto

Cornell University was founded in 1865 and has educated many exceptional women. The first woman was admitted in 1870, and a women’s dorm, Sage Hall, was built in 1875. In 1890, Jane Eleanor Datcher was the first Black woman to graduate with a bachelor’s degree. Cornell’s first woman Assistant Professor was Anna Comstock, a naturalist, appointed in 1899. She was demoted due to complaints by trustees, however, and was not reinstated to professor status until years later.

The training of women in paleontology at Cornell in the early 1900s was almost solely the result of the efforts of Gilbert Harris (1864–1952). Gilbert Harris was a professor of geology at Cornell from 1895 to 1934. Under his mentorship, Carlotta Maury (Ph.D. 1902), Katherine Palmer (Ph.D. 1925), and other women earned their Ph.D.s.

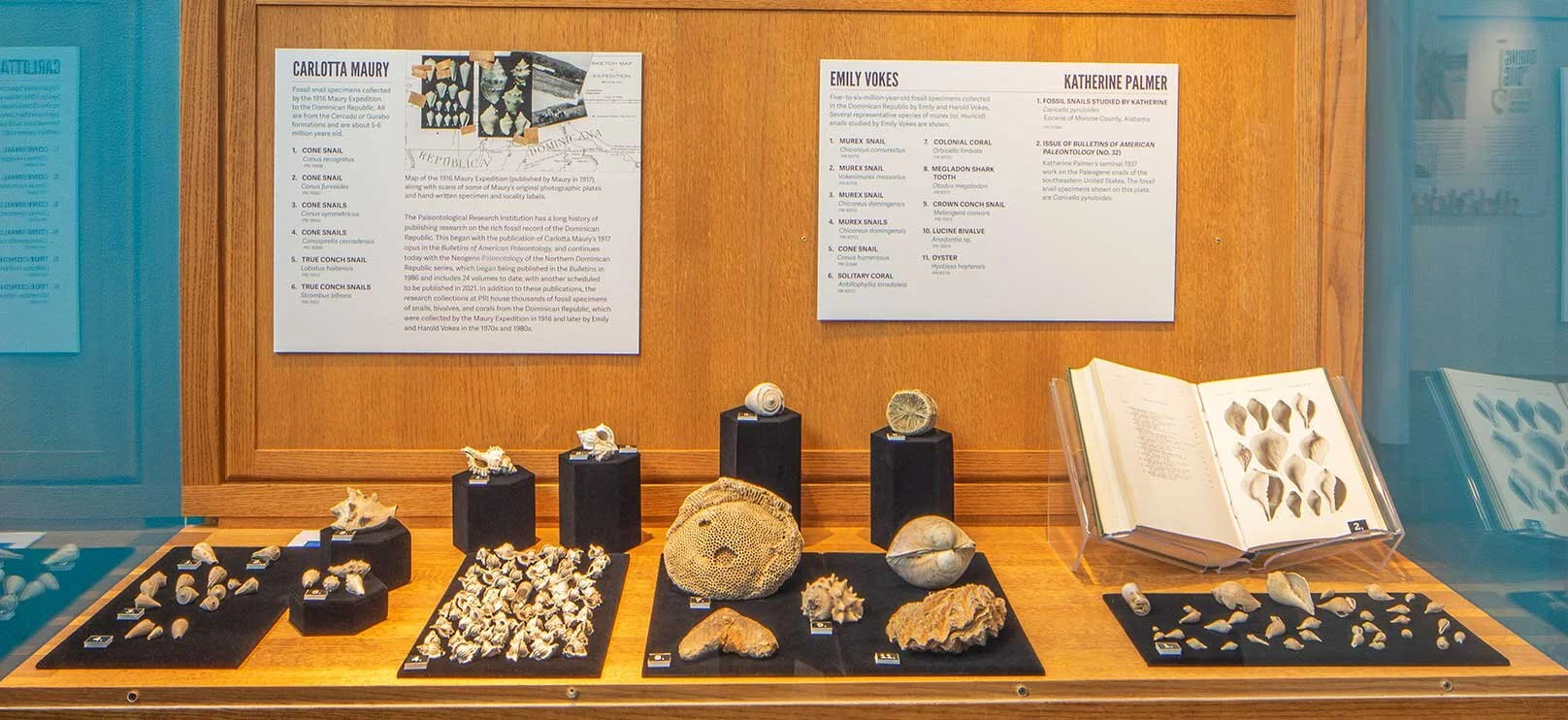

Display of fossil specimens related to Carlotta Maury, Emily Vokes, and Katherine Palmer, Daring to Dig exhibit at the Museum of the Earth, 2021. Photo by Jon Reis.

In 1895, Gilbert Harris began the Bulletins of American Paleontology, which is currently the longest-running, continuously published paleontology journal in the western hemisphere. He founded the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI) in 1932. PRI was originally located on the east side of Cayuga Lake near Cornell, but moved to its current location in the 1960s when Katherine Palmer was Director.

Gilbert Harris and his students were invertebrate paleontologists, or paleontologists who study animals without backbones. Most invertebrate paleontologists study marine (ocean-dwelling) invertebrates. Some types of marine invertebrates are still alive today, such as sponges, corals, mollusks (clams, snails, squids, etc.), and echinoderms (crinoids, starfish, sand dollars, etc.). Other types are completely extinct, like trilobites and eurypterids (sea scorpions).

While invertebrate paleontology has historically been taught as part of the geology program at Cornell, paleobotany, the study of fossil plants, has been taught as part of the botany (plant biology) program since the 1920s. Harlan P. Banks, whose research was on land plants from the Devonian period (about 419 to 359 million years ago), was a professor at Cornell from 1949 to 1978. His students included Patricia M. Bonamo (Ph.D. 1966) and Judy Skog (Ph.D. 1972).

Featured Paleontologists

Documenting Biodiversity

A researcher considering the relationships among dinosaurs. Illustration by Alana McGillis.

The part of biology devoted to documenting and classifying all forms of life is called systematics. One of the main goals of systematics is to describe each different species on Earth. A species is a group of individuals—whether they are animals, plants, fungi, algae, or other forms of life—that come from the same ancestors, share similar features, and can reproduce with each other. To name a new species, a scientist must first recognize it and observe its unique features. Then, the scientist must describe the new species in a way that other scientists can understand and use.

Paleontologists who specialize in systematics study fossil species and document the diversity of fossil life over time. To describe fossil species, paleontologists often rely on large, well-organized collections of fossil specimens held by universities or museums. They must compare, sort, and measure these specimens so that they can identify different species in the fossil record.

In some respects, the task of describing a species today is very similar to how it was done decades or even a century ago. It still demands careful observation and study of specimens, which are typically held in museums. Fossils are often illustrated with photographs or drawings. Although new techniques and technologies have brought improvements, tools of the trade still include calipers and rulers for measuring, microscopes for observing small specimens, and cameras to document specimens.

Featured Paleontologist

The Publication Process

Communicating research findings is a critical part of science. Illustration by Alana McGillis.

Communicating research findings is a critical part of science. Scientists can communicate their findings in a few different ways, such as giving presentations at scientific meetings. For research results to become part of the permanent scientific record, they typically have to be published in a scientific journal following a formal process. Both Katherine Palmer and Emily Vokes edited journals during their careers.

When a scientist thinks she has discovered something new, she usually writes a manuscript about the new finding. A manuscript is a draft of an article. The scientist then submits her manuscript to a scientific journal. The editor of the journal sends the manuscript to other scientific experts. These experts comment on the findings and interpretations in the manuscript. The expert evaluators are also asked to recommend whether an article should be accepted, revised, or rejected. This process is called peer review.

Generally, only articles published in peer-reviewed scientific journals are treated as reliable. This is because peer-reviewed papers have been expertly vetted and judged to be sound. While the process is not perfect, the peer-review system helps ensure that scientific claims are evaluated before publication. Journals and their editors thus play a major role in the process of science.

Much of the history of science is about who published what, when they published, and who did not publish or published too late. Very early in the history of paleontology, women may not have published their findings because they were excluded from giving presentations or publishing their work. Studying the history of science helps us to recognize and acknowledge their contributions today.

Field Work in Paleontology

For many paleontologists, fieldwork is one of the most exciting and rewarding aspects of their work. Early paleontologists would have arrived at their field sites on foot or on horseback. Today, many paleontologists travel to their field sites in 4-wheel-drive trucks. Helicopters are used to access remote field sites in rugged terrain, and special ships equipped with drill rigs are used to recover seafloor samples. Whereas in the past paleontologists may have found promising dig sites using painstakingly drawn geological maps, today aerial photography or satellite surveys help.

In the early 1900s, the typically middle- and upper-class white women who pursued paleontology as a career faced social barriers to participating in fieldwork. In response, they made their own specialized clothes, learned to shoot a gun, and recruited other women to accompany them on expeditions to avoid appearing “improper.”

Many of the barriers that kept women out of the field or limited their participation in the past have been removed or reduced. However, substantial challenges remain. Field sciences often still have a reputation as a man’s world, which can make women feel like outsiders, especially because women may have unique needs when working in the field. Women of color and LGBTQ+ scientists may especially avoid fieldwork based on fears for their safety. Field localities may not be accessible for women with disabilities, and pregnant women or those caring for young children may find it difficult to participate in field experiences.

Today, increasing awareness of the barriers that keep some groups from participating in fieldwork is leading many to look for solutions to accommodate more people’s needs, ensure their safety in the field, and provide a welcoming environment for all.

Stereotypes & Bias

While social roles for women are considerably broader and more flexible than they were in the past, women are still judged according to the social expectation that they be feminine. Paleontology—especially being a field paleontologist—is associated with traits that are typically considered masculine. This means that women often have to overcome biases about their interests and abilities in order to be taken seriously.

Sometimes, biases are explicit, or stated and felt openly. Oftentimes, however, biases are implicit. This means that they are biases that we hold and act on without consciously realizing it. Before you came to this exhibit, who would you have imagined as a paleontologist? An Indiana Jones type? Maybe Alan Grant from Jurassic Park or Owen Grady from Jurassic World? Having seen the exhibit, who would you imagine now?

While overcoming biases may seem daunting, we can combat them if we recognize that they exist. Recent projects—like the book and film The Bearded Lady Project and the film Picture a Scientist—seek to challenge stereotypes of science as a white male profession.