Women in Industry

Several developments in the late 1910s to 1920s led to a sudden increase in women working as paleontologists in the oil industry. The first was demand. World War I and the expansion of automobile ownership increased the market for oil. The second was a shortage of men—who were needed to serve in World War I (1914–1918) and, later, World War II (1939–1945)—to fill industry roles. The third was the discovery that microfossils could help find oil. This discovery, which helped make oil companies rich, was made by women: Esther Applin, Alva Ellisor, and Hedwig Kniker.

Restrictive social roles also helped to steer women into micropaleontology. At the time, the kind of lab work associated with micropaleontology was more socially acceptable for women to do than other areas of geology. The use of scientists as consultants in the petroleum industry was also a way for women to maintain professional careers in geology at a time when this was not always viewed as appropriate. Consulting allowed these women the flexibility to have careers while fulfilling the cultural expectations of their traditional roles as wives and mothers.

This relatively friendly situation for women in science was not permanent. World War II saw a general expansion in employment opportunities for women. After the war, many women exited or were pushed out of the workforce and opportunities for women shrank.

Illustration by Alana McGillis.

Micropaleontology

Micropaleontology is the study of very small fossils, called microfossils. Microfossils are so tiny that they must be examined with a microscope in order to see their details. Some microfossils are the hard coverings—shells, plates, or other structures—of single-celled marine organisms called protists. Examples of protists that can be found as microfossils include foraminifera (forams), radiolarians, coccolithophores (coccoliths), dinoflagellates, and diatoms.

Forams were especially important in oil exploration in the early 1900s and are used to measure ancient climate change today. A foram is an amoeba-like, single-celled organism protected by a tiny shell. Forams live in saltwater. Most species live on the seafloor, although some live in the water column. Foram shells are often preserved in the fossil record.

Micropaleontologists often break down the rocks that contain microfossils to free the fossils from the surrounding rock matrix. Once freed, the fossils can be studied. The tools used to study microfossils depend on the size of the fossils. Some tools for studying larger microfossils like forams include picking trays for sorting, paintbrushes for picking up specimens, vials for storage, and microfossil slides for examining specimens.

Micropaleontologists do their work using microscopes. The type of microscope chosen depends on the type of specimen. A stereomicroscope is a lower-magnification microscope used to study three-dimensional specimens. A compound microscope is a higher-magnification microscope that is typically used to study specimens mounted on standard glass slides. A scanning electron microscope, or SEM, is a specialized microscope that uses an electron beam to make an image of a specimen. SEMs are especially good for examining fine surface features.

Micropaleontologists must be patient and detail oriented. The best micropaleontologists hone their fossil identification skills so that they can rapidly identify the many microfossil species that may be preserved in a single rock sample.

Recreation of micropaleontologist Esther Applin’s office. This display includes some of Esther’s real equipment.

Biostratigraphy

This antique tricone bit that was used to drill for oil. The cones rotated, cutting through the rock.

Biostratigraphy is the science of using fossils to date layers of rock. Fossils are very useful for determining the ages of rocks because they are the remains of ancient species that evolved, survived, and went extinct.Because each fossil species existed for a limited time interval, fossil species can be used to tell time in the rock record. In fact, most of the boundaries on the geologic time scale are based on the first or last appearance of particular species.

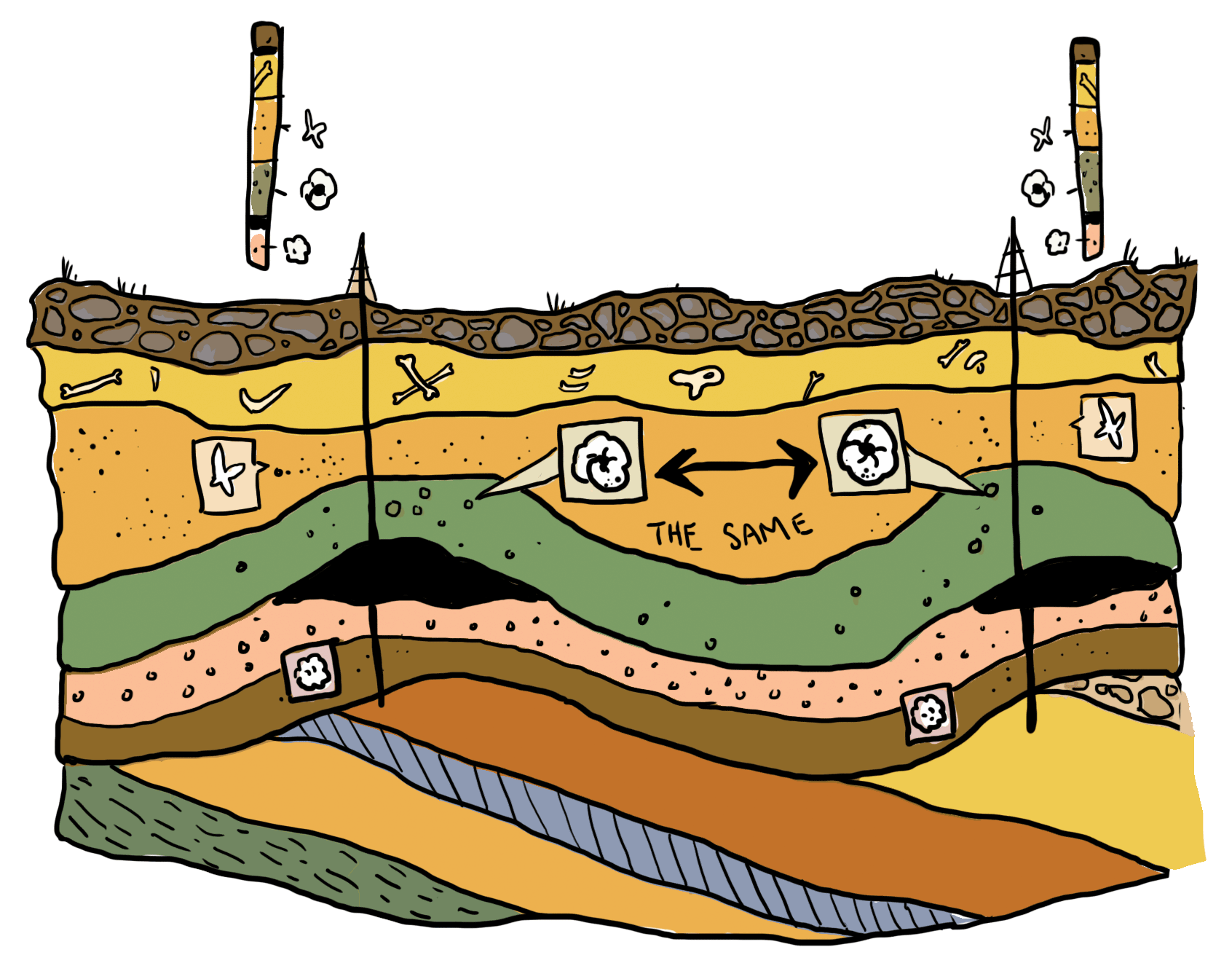

Some ancient species were widespread and can be used to correlate rock layers from different regions or even different continents. Correlating is matching up layers of rock that come from different places but are the same age. For example, if you find the same fossil species in rock layers in the United States and China, you know that the rocks are about the same age. This is true even if the rock types are different, like sandstone and limestone.

From the 1920s to 1940s, many women worked for oil companies as paleontologists. Oil companies drill deep wells into the Earth to pump oil out. To know how deep to drill, oil companies need to identify rocks that are the right age to contain oil. In the early 20th century, the only way to date rocks was using fossils. Paleontologists identified fossils from well samples, which allowed new reserves of oil to be discovered.

Drawing showing how biostratigraphic correlation works. Illustration of Alana McGillis.

Work-Life Balance

“In the past and at present several women in geology have been married and made outstanding names for themselves. Others trained in the science have married geologists and thereby helped in mutual interest and endeavors. The individual, in all cases, has to find the equilibrium of her situation.”

– Katherine Palmer (1976) “Role Models”

In the early to mid-20th century, professional jobs in the United States were designed around the ideal of a white man who was fully committed to his work. He had a homemaker wife to take care of the house and children. Professional women were often expected to give up their jobs upon marriage, a practice called a “marriage bar.” Employers did not worry about accommodating mothers in the professional workplace because mothers were not supposed to be working.

While marriage bars are now illegal and many professional women have children, conflicts between the concept of the “ideal worker” and the reality of women’s lives still exist. Long training periods, insecure employment during the early career years, inadequate maternity leave, and difficulties arranging child care can make having and raising children challenging for American women scientists. They often have to patch together their own solutions to balance work and family responsibilities.

In a shift from the past, however, good employers understand that they have a role to play in making the science career path more equitable for everyone. Finding the best way to balance having a home life and a career is a continuing challenge for many scientists in the 21st century.

Featured Paleontologists

Women at the USGS

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) is part of the U.S. Department of the Interior. It was founded in 1879 to document the geology and mineral resources of the United States. Its mission has expanded over the years, and it is now a broader natural resources agency. The USGS today studies water resources, ecosystems, natural hazards (for example, earthquakes and volcanoes), and energy resources. The agency also pursues its traditional mission of documenting the geology, minerals, and topography of the United States.

Florence Bascom (1862–1945) was the first woman hired as a geologist by the USGS in 1896. Florence was also a faculty member at Bryn Mawr, a women’s college in Pennsylvania, and an important mentor to younger women geologists. Several of her former Bryn Mawr students, including paleontologist Julia Gardner, began careers with the USGS in the early 20th century. Even so, the number of women scientists at the USGS and in the federal government at that time was small. As of 2018, over 3,000 women work there, making up about a third of the workforce.

The work of paleontologists at the USGS—like Julia Gardner, Esther Applin, and Anita Harris—facilitated the development of petroleum resources in the United States.