Women at the Forefront of Modern Paleontology

Women in the Late 1900s to Today

Illustration by Alana McGillis

In the late 1900s, the role of women in society underwent a dramatic shift. In the 1960s, the first birth control pill was approved for sale in the United States, and new federal laws banned employers from discriminating against workers on the basis of sex or race. The Association for Women Geoscientists (AWG) was formed in 1977, and the National Association of Black Geologists and Geophysicists (NABGG) was founded in 1981.

As women began to gain more freedom, they also began to enter the workforce in greater numbers and to pursue higher education and professional careers. The professional working world, however, was not designed with women in mind. Just like in the early 1900s, women in the late 1900s and even today often have had to make compromises and find work-arounds to pursue their careers. They have faced unequal treatment in the workforce, in the lab, and in the field.

Representation of Modern Women

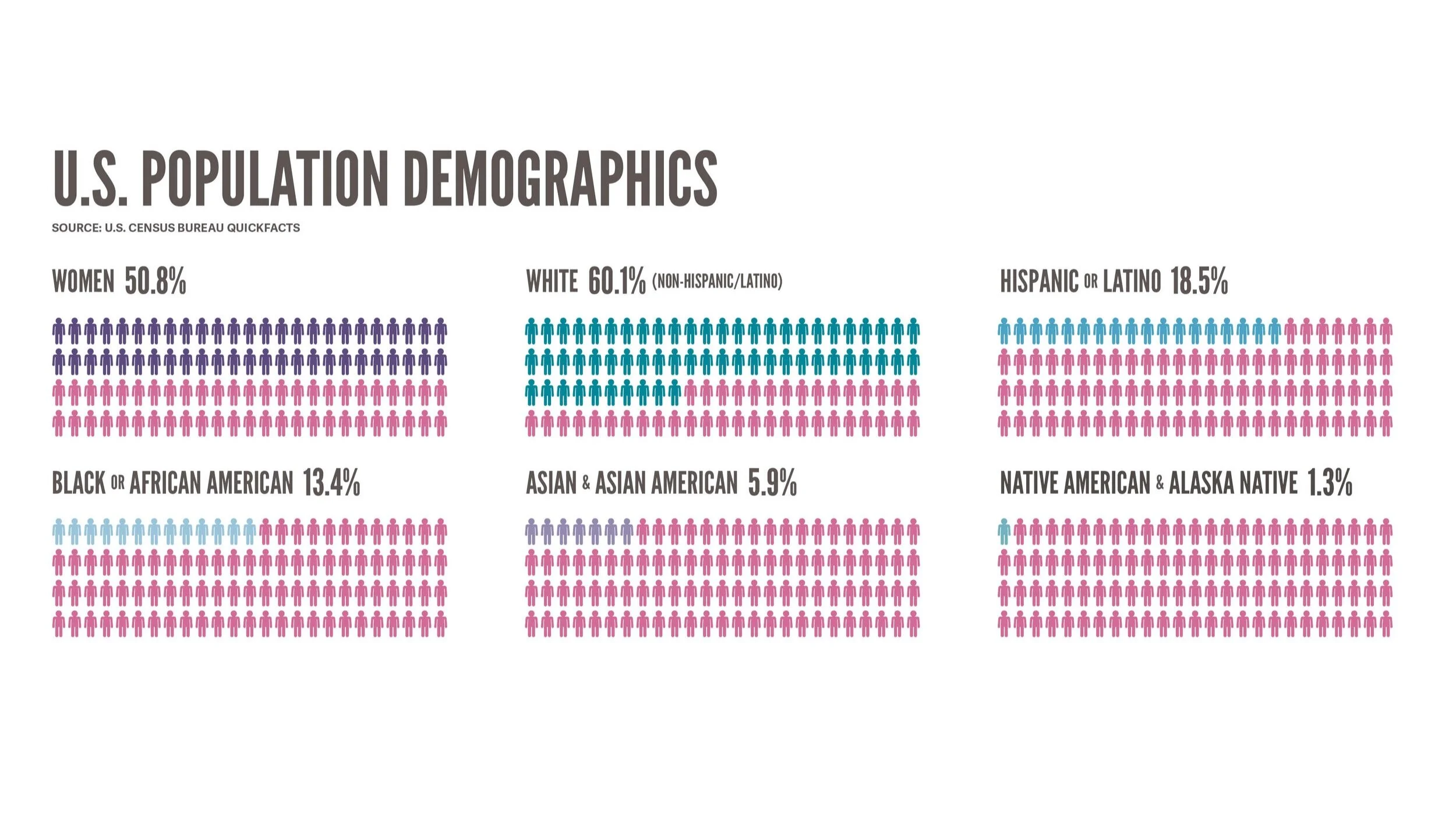

U.S. Population Demographics: Women = 50.8%, White (non-Hispanic/Latino) = 60.1%, Hispanic or Latino = 18.5%, Black or African American = 13.4%, Asian & Asian American = 5.9%, Native American & Alaska Native = 1.3%. Source: U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts.

Paleontological Society Membership and Awards data. Membership: 1980s, 14% women & nonbinary; 2019, 36% women & nonbinary. Awards: Schuchert Award, the early career award: 8 awards to women out of 49 total awards from 1973 to 2020. Paleontological Society Medal, highest award: 4 awards to women out of 56 awards from 1963 to 2019.

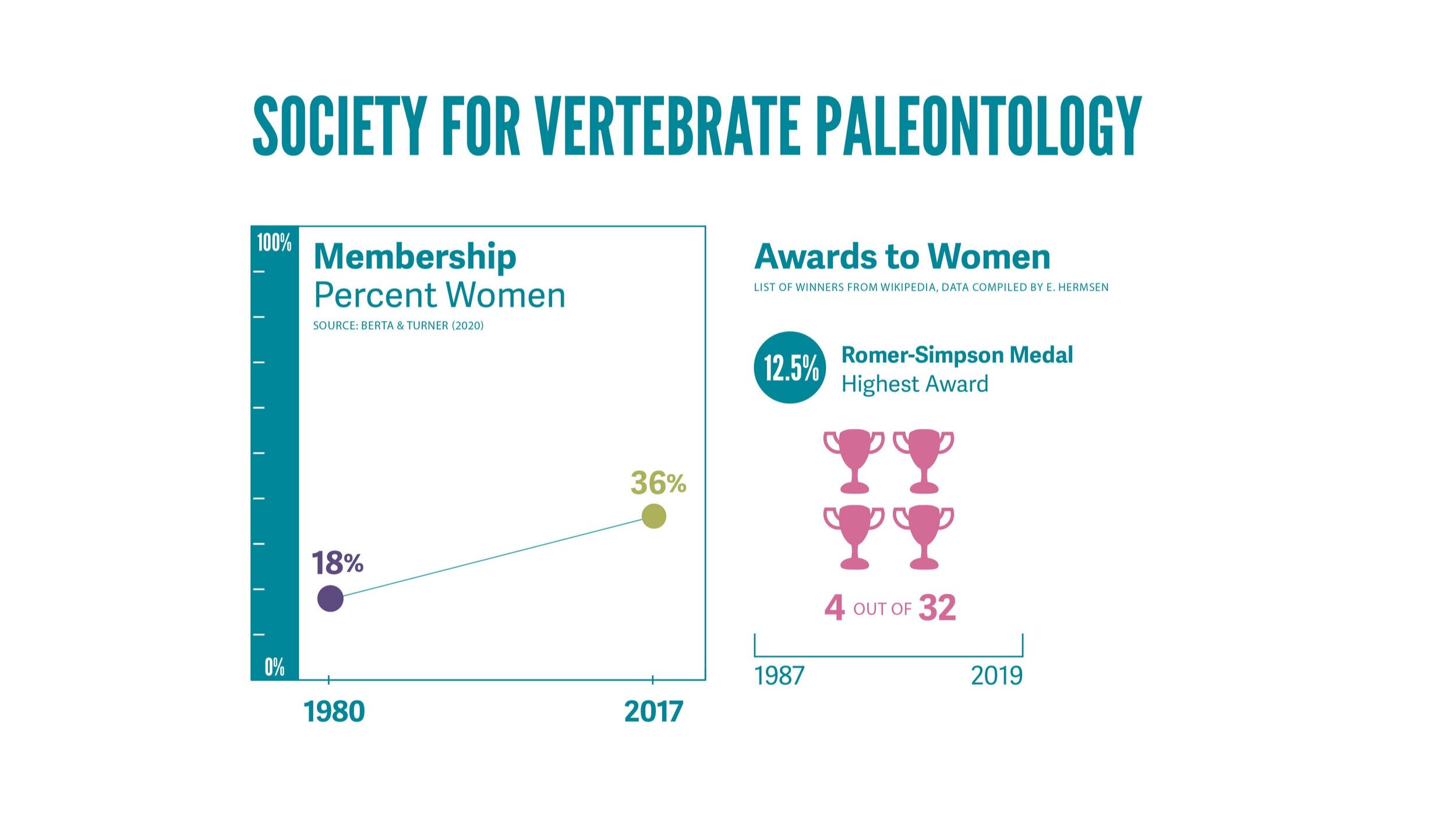

Society for Vertebrate Paleontology Membership and Awards data. Membership: 1980, 18% women; 2017, 36% women. Awards: Romer-Simpson Medal, highest award: 4 awards out of 32 total awards from 1987 to 2019.

Women in professional positions at colleges and as curators data. Representation of women employed as paleontology faculty at geoscience departments in U.S. 4-year colleges and universities: about 25%. Representation of women employed as paleontology curators in the U.S.: about 18%.

U.S. geoscience PH.D. demographic breakdown, covering the period from 1973 to 2016. Total Ph.D.s awarded: 22, 614, 73% to men, 27% to women. From 1973 to 2016, 241 geoscience Ph.D.s were awarded to Latina women, 69 to Black women, and 20 to Native American women. Source: Bernard & Cooperdock (2018) “No progress in diversity in 40 years.”

Topics in Modern Paleontology

Daring to Dig exhibit display for Women at the Forefront of Modern Paleontology, 2021. Photo by Jon Reis.

Paleobiology

From the 1700s to the mid-1900s, paleontology was dominated by systematics and biostratigraphy. In other words, most paleontologists described and documented various types of fossils and used fossils to date rocks. Much less attention was given to understanding the biology of the once-living organisms that were fossilized or the ecological and evolutionary contexts of these organisms.

Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, however, a new generation of paleontologists increasingly applied data from fossils to evolutionary, biological, and ecological questions. This trend coincided with the decline of paleontology in the oil industry. The resulting discipline became known as paleobiology. Paleobiology is a subfield of paleontology that studies fossils as biological organisms rather than geological objects.

Paleoecology

Paleoecologists study the interactions between extinct organisms and the ancient environments in which they lived. These environments may be on land or in the water. Paleoecologists may study a wide variety of research questions.

One question a paleoecologist might ask is: How did ancient predators and their prey interact? Behavior may seem like a hard thing to study infossils. However, fossil shells often have damage caused by predators, like break marks or drill holes. If a shell shows signs of repaired damage, it indicates that the prey survived the attack and later healed.

Another question a paleoecologist might ask is: What did extinct animals eat? There are different ways to figure this out. One way is to look at the stomach contents of an animal—what was preserved in its gut when it died? Another is to examine coprolites: fossilized animal poop. Coprolites sometimes contain bits of meals in the form of undigested plant and animal parts.

Micropaleontology & Deep-Sea Sediment Cores

Layers of sedimentary rock are the pages of Earth’s history book. These layers record the motion of the continents, the history of environmental change, and the history of life on Earth. Since 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered by the ocean, most of the sedimentary record is difficult to reach.

In 1968, scientists formed an international group to explore the ocean floor through deep-sea drilling. The International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) has sampled the floor of the ocean in hundreds of locations, making the samples available for all scientists to study. Paleontologists have examined mass extinction events, the limits of life in the deep ocean, and past climate changes recorded by fossil organisms, such as forams, preserved in deep sea sediments.

Palynology

Palynologists specialize in microfossils called palynomorphs. Palynomorphs are freed from the rocks that they are encased in using chemicals that would destroy many other types of microfossils.

Palynomorphs come from several different groups of organisms. Pollen is produced by plants. Spores are made by fungi, algae, and plants. Dinoflagellate cysts are resting structures made by single-celled, aquatic organisms called dinoflagellates. Palynomorphs that cannot be assigned to a known group of organisms are called acritarchs.

Palynologists use palynomorphs to study biostratigraphy. They can also be used to reconstruct ancient environments. Acritarchs—which occur throughout the fossil record—are especially important to understanding life before the first animals.

Paleobotany

Paleobotany is the study of fossil plants. Whole plants are usually not preserved in the fossil record. Rather, fossil plant parts are often found in isolation. These parts may be pieces of wood, individual leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, or other structures.

Some paleobotanists work on fossil plant systematics, meaning that they document ancient fossil plant diversity and classify species into larger groups based on their evolutionary relationships.

Paleobotanists also use plants to reconstruct ancient environments. The types of plants that are preserved at a particular fossil site indicate what the habitat was like, for example whether it was a crowded forest or more open environment. Fossil leaves of flowering plants can be used to estimate ancient temperatures and rainfall.

Isotope Records

You are what you eat, and isotopes prove it. Isotopes are types of atoms that can be used to measure environmental change. Atoms are made up of three kinds of particles: positively charged protons, neutral neutrons, and negatively charged electrons. An element—such as carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, or oxygen—always has the same number of protons, but can have different numbers of neutrons and electrons.

Isotopes of an element have different numbers of neutrons. For example, all carbon atoms have six protons, but carbon isotopes may have six, seven, or eight neutrons. Because each isotope has a different number of neutrons, it also has a different mass.

Isotopes with different masses behave differently in the environment and will leave different chemical signatures when they are used to make tissue, shell, or bone. Isotopes of carbon and nitrogen are used to study diet and food chain dynamics. Isotopes of oxygen preserved in fossils are especially useful in studying ancient temperature changes in the ocean and atmosphere.

Science Communication & Outreach

Much of the research that scientists do is reported in scientific journals that are meant to be read by specialists. These technical reports are often filled with obscure vocabulary that can be hard to understand, even for scientists who are specialists in other fields. Science communicators translate scientific findings into terms that can be understood by a wide range of people, making science accessible to everyone. The goals of science communicators are to inform, inspire, and educate.

Science communicators may reach their audiences online, in print, or in person. Many are active on social media. They may write articles that are printed in science magazines and posted on websites. They may even write full-length books. They may visit schools, camps, libraries, and other public venues to talk directly to people and answer their questions.

Specimen Databases

Many university and museum fossil specimen collections have electronic databases to catalogue their specimens. Electronic specimen catalogues allow institutions to keep track of what is in their collections and to make sure that the information associated with each specimen, like where it was found and who found it, is stored somewhere. Some institutions have private databases, whereas others make their databases available online where they can be searched by the public.

Several projects have been started to aggregate, or bring together, data from multiple collections so they can be more effectively used by researchers. Projects like iDigBio and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) are powerful tools that let researchers search multiple collections simultaneously, look at images of specimens, make maps of places where specimens were found, and download datasets.