How do we know ancient temperatures and levels of carbon dioxide (CO₂)?

We have excellent CO₂ data from instruments and satellites going back to the 1950s, and Earth surface temperature data going back to the late 1800s. Instrumental data are spotty prior to the 19th century, but luckily nature has provided us with climate proxies: records from the past that preserve Earth’s climate history in tree-rings, fossils, sediment, rocks, glaciers, and ice sheets!

This animation shows how far back in time we can extract past climate and CO₂ data from proxies.

Click the “Present” button to begin, and then click on the arrows at the bottom of the screen to move through the animation.

Ancient climate and CO₂ clues buried in sediment

Most of what we know about the history of Earth’s climate comes from layers of sediment. Deep sea cores of sediment up to thousands of meters long contain especially well-preserved records, going as far back as 200 million years.

Most of the climate information within the cores comes from the shells of single-celled plankton called foraminifera that sank to the ocean bottom after death. The ratio of two varieties (isotopes) of oxygen atoms in their shells is controlled by water temperature. Other chemical data from cores provide information on CO₂ concentration and ocean acidity.

The 3D image below is of a rock core from the Lockport Dolostone near Buffalo, New York. It is from the Middle Silurian Period, about 430 million years ago.

Click on the image and move your pointer around to view the rock core from different perspectives. Scroll to zoom in and out.

Students visiting the Gulf Coast Repository of the International Ocean Discovery Program at Texas A&M University. The repository houses over 60 miles of sediment and rock cores retrieved from beneath the seafloor.

Photo: Kusali Gamage

This photo is a piece of a sediment core from the JOIDES Resolution, an ocean-going ship that has collected many sediment cores that record Earth’s past climate. It can take twelve hours just to lower a drill from a ship to the ocean floor!

This core shows the result of an asteroid impact 66 million years ago that ended the Cretaceous period. The dark layer contains glassy particles that condensed from the hot vapor cloud created by the impact. The orange layer above this contains dust and ash fallout.

Photo: joidesresolution.org, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

Clam shells preserve the climate

Clam shells have annual growth bands, and the spacing between the bands depends on the environment during the time when the growth bands formed. Chemical analysis of clam shells can reveal the water temperature during the winters and summers when the clams lived. We can learn about the seasonality of climates from tens to hundreds of millions of years ago from fossil clams.

The 3D image below is of a fossil Quahog (Mercenaria) shell (Plio-Pleistocene of southern Florida.) The ridges trace the growth of the shell outward from the hinge. Although the ridges might seem similar to tree rings, one ridge does not necessarily correspond to one year.

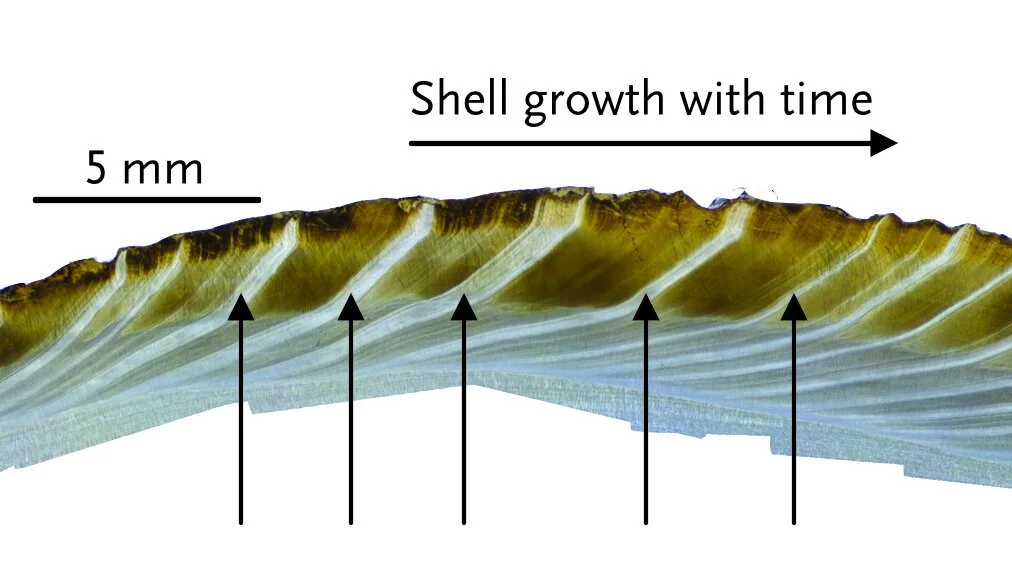

Slice through a clam shell, polished and magnified. The arrows point to annual growth bands.

Photo: Linda Ivany

Fossil leaf edges tell us about temperature

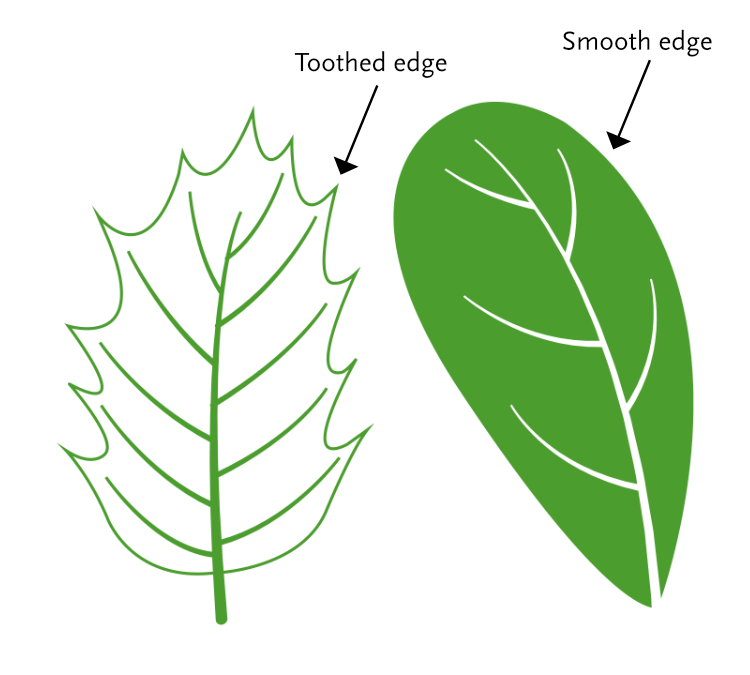

In warmer climates, a higher proportion of leaves tend to have smooth edges. Conversely, in cooler climates, most leaves have toothed edges. We can use the relative proportions to estimate ancient temperatures.

Examples of leaves with smooth and toothed edges

Below: leaf fossils with smooth edge and toothed edge. Which leaf is more likely to come from a tree in a warmer climate?

If you go outside today, take a look at the leaves you see.

What do you notice about their edges?

Past temperatures and CO₂ locked in ice

Most of the data points you see on the timeline graphs in this exhibit came from climate records trapped in ice!

Glacial ice forms from layer upon layer of seasonal snow. Ice cores are long cylinders of ice that have been drilled in the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, as well as some mountain glaciers. Ice cores hold records of past temperatures and atmospheric CO₂, which scientists can extract from chemical analysis of the ice itself, as well as CO₂ trapped in air bubbles within the ice. The longest of these records goes back over 800,000 years.

Wide tree rings in wet years

You can tell the age of a tree by counting its rings. Tree rings also record the climate during the time when the tree grew. When the climate is warm and wet, trees tend to grow more rapidly, and the spacing between rings is wider than during cold, dry years.

The tree cores shown here were collected from two Eastern hemlock trees in the Paleontological Research Institution’s Smith Woods, an old growth forest in Trumansburg, New York.

You don’t have to cut down a tree to study its rings. Scientists use an instrument called an increment borer to collect thin cores of wood from living trees, and this causes no harm to the tree.

Researcher collecting tree core in Smith Woods. Photo: Carol Griggs

Dig deeper into climate change and energy on the Learn More page of this exhibit.

Image credits: on Learn More page