Mary Buckland

Mary Buckland

Mary Buckland

1797–1857

Mary Morland Buckland was a British paleontologist, collector, and science illustrator.

“She is an admirable fossil geologist, and makes models in leather of some of the rare discoveries.”

–Description of Mary Buckland by Miss Caroline Fox (1839), as quoted in The Life and Correspondence of William Buckland (1894)

Mary’s mother died when she was very young. Her father remarried, and Mary was brought up mainly in the household of Sir Christopher Pegge. In her teenage years, Mary had a clear passion for paleontology. She exchanged letters with Georges Cuvier—who is often called the founder of paleontology—and created fossil illustrations for his work. The Pegges supported and nurtured her interests.

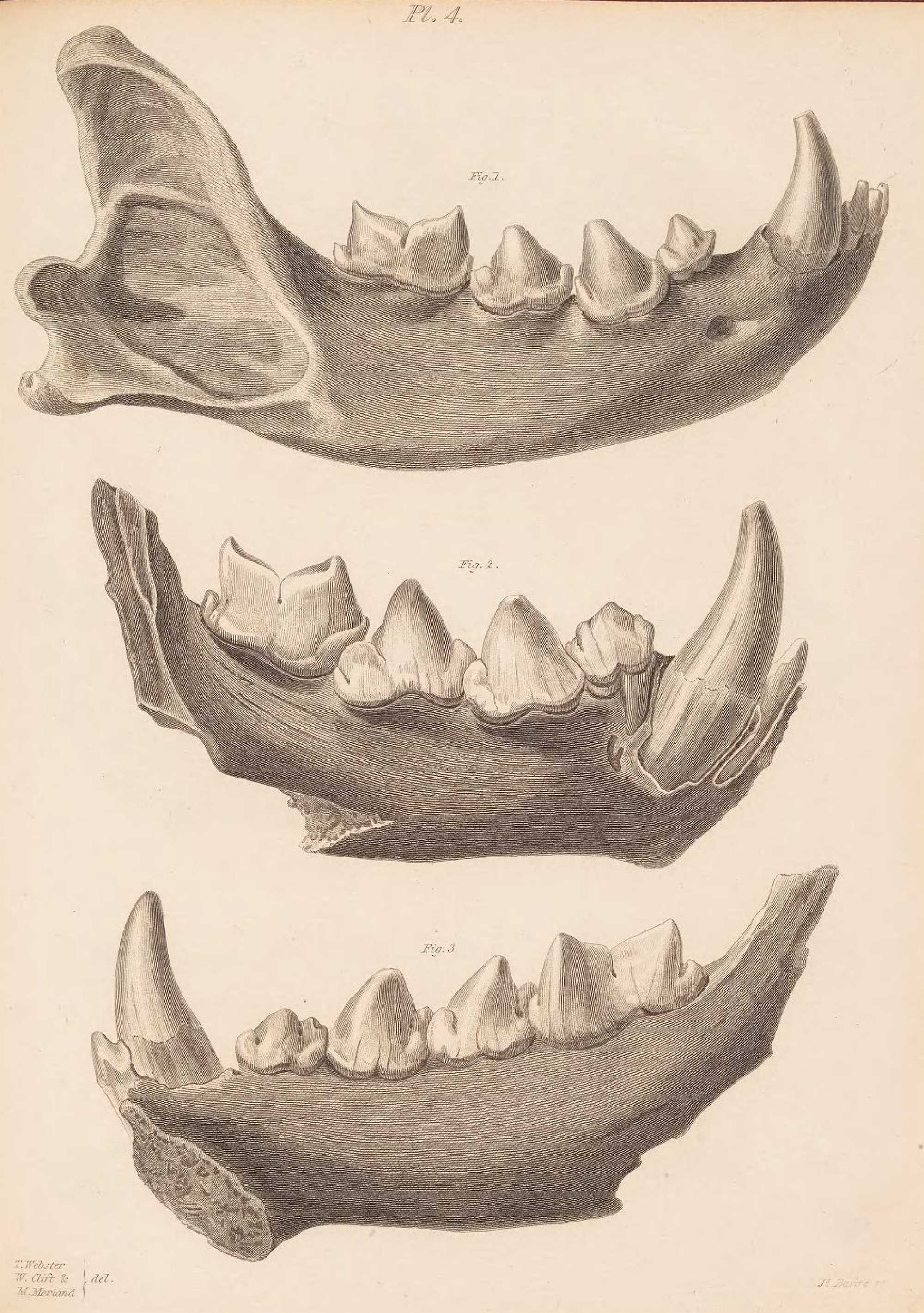

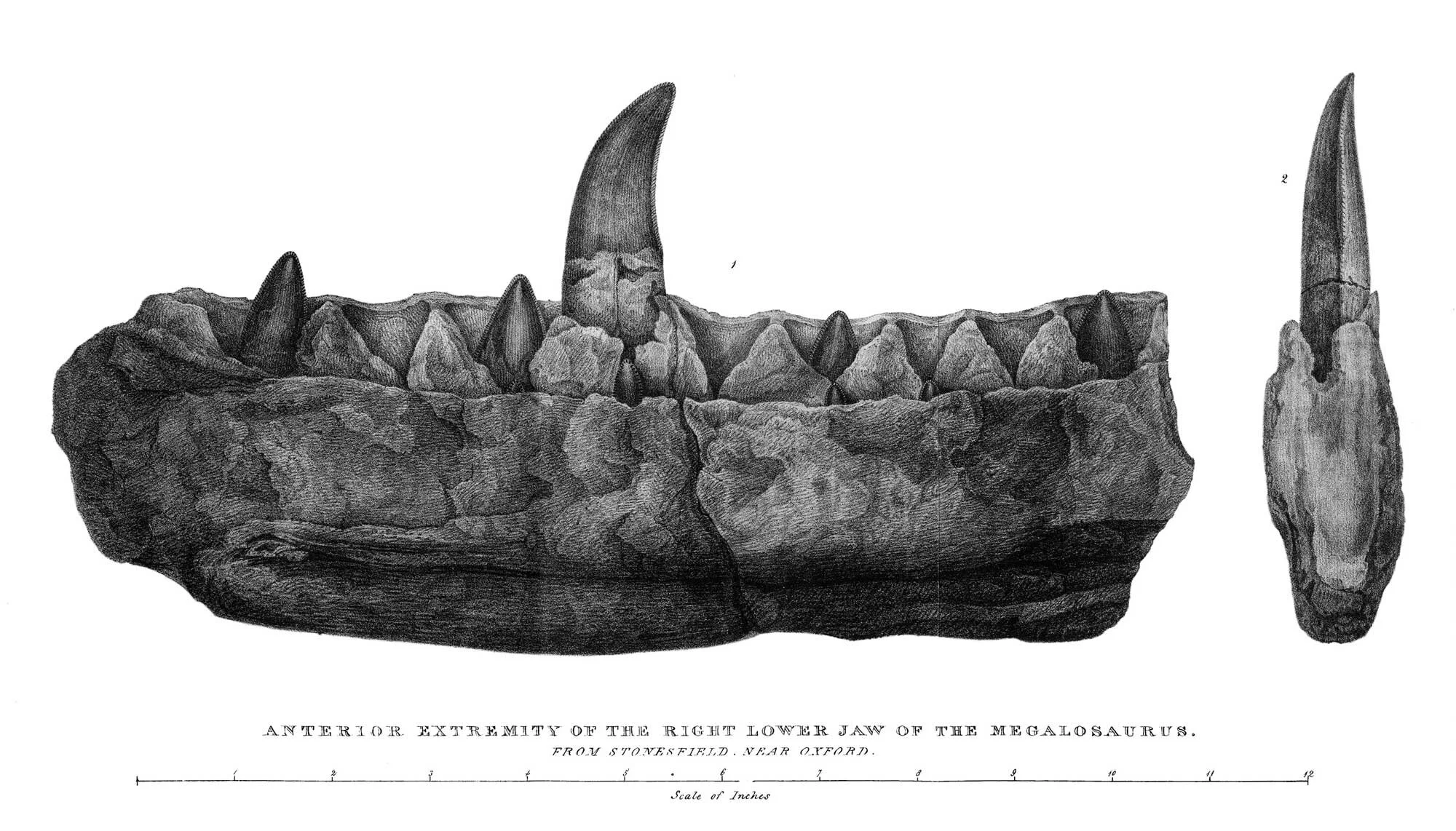

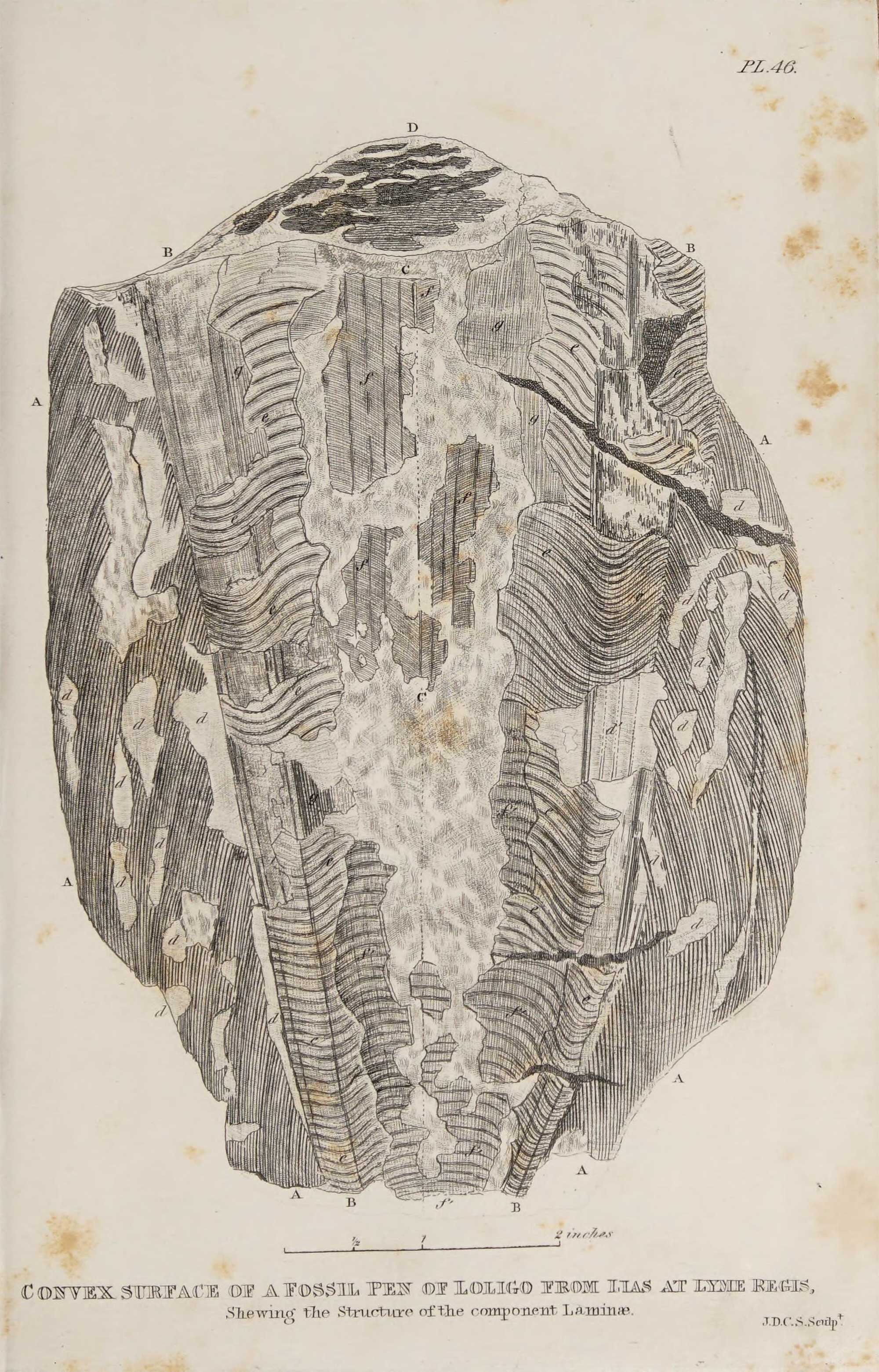

As a young woman, Mary became a well-known scientific collector and illustrator. As Mary Morland, she produced illustrations for some of the works of her future husband, William Buckland. These include drawings of Megalosaurus—the “great fossil lizard of Stonesfield”—which was the first dinosaur to be scientifically described in 1824. She also made drawings of extinct animals found in a cave in England.

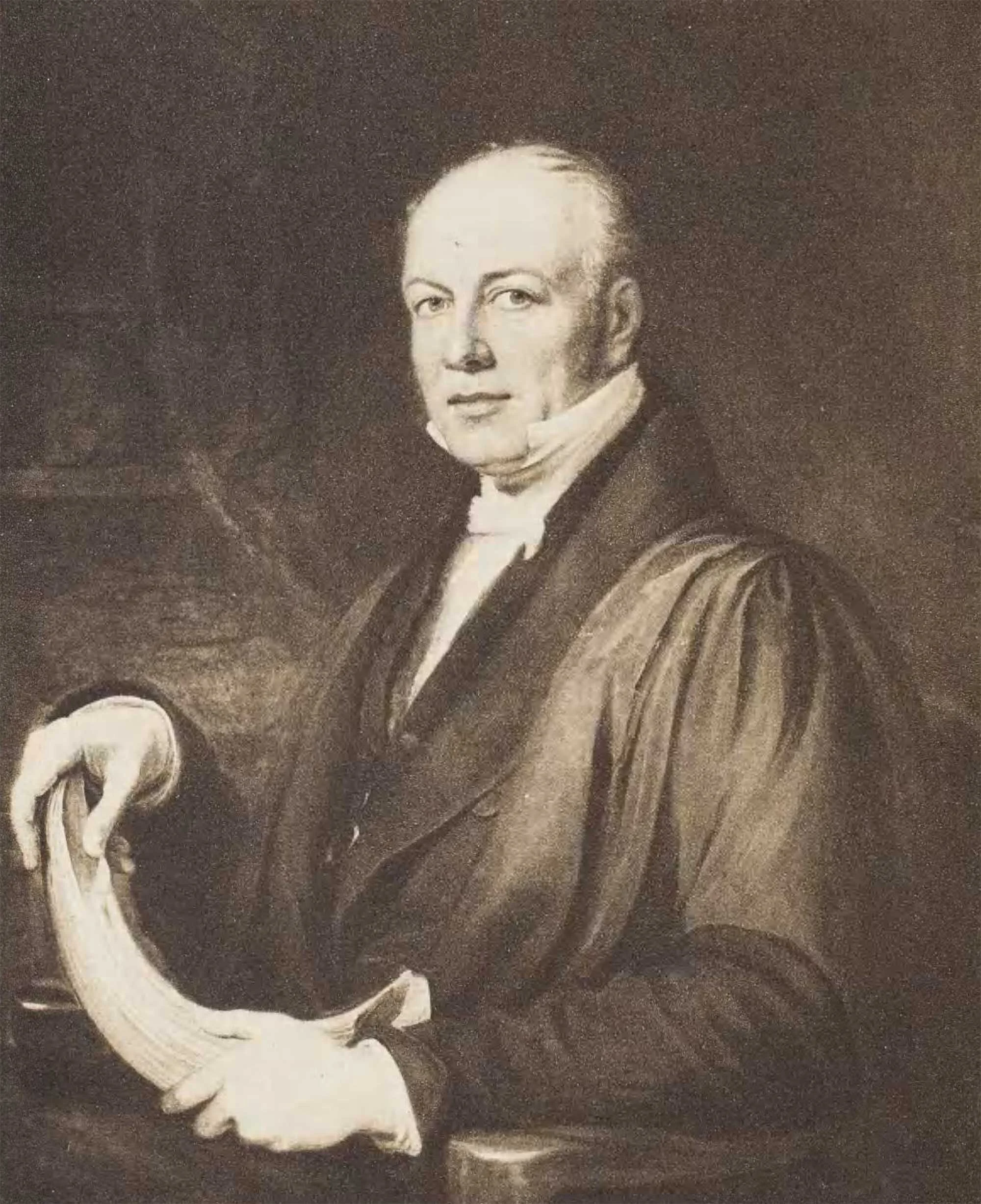

Mary is said to have met her husband William (1784–1856) while both were traveling in a carriage. The story is recounted in The Life and Correspondence of William Buckland (1894), which was written by William and Mary’s daughter, Elizabeth Gordon:

“Davies Gilbert tells us that Dr. Buckland was once travelling somewhere in Dorsetshire, and reading a new and weighty book of [Georges] Cuvier’s which he had just received from the publisher; a lady was also in the coach, and amongst her books was this identical one, which Cuvier had sent her. They got into conversation, the drift of which was so peculiar that Dr. Buckland at last exclaimed, ‘You must be Miss Morland, to whom I am about to deliver a letter of introduction.’ He was right, and she soon became Mrs. Buckland.”

—Miss Caroline Fox (1839), as quoted in The Life and Correspondence of Willam Buckland (1894)

They married in 1825 and lived in Christ Church. William was eccentric. He imitated the walks of ancient animals and ate unusual foods, like crocodile. The Buckland house was chaotic, every room filled with scientific books and papers. The couple had nine children, five surviving into adulthood. A description of the Buckland household says:

. . . besides the stuffed creatures that shared the hall with the rocking-horse, there were cages full of snakes, and of green frogs, in the dining-room, where the sideboard groaned under successive layers of fossils, and the candles stood on ichthyosauri’s vertebrae. Guinea-pigs were often running over the table; and occasionally the pony . . . would push open the dining-room door, and career round the table, with three laughing children on his back . . .”

— George C. Bompas (1886) Life of Frank Buckland (Frank was Mary and William’s son)

Silhouette of William, Frank (their eldest son), and Mary Buckland. Source: Gordon (1894) The Life and Correspondence of William Buckland, D.D., F.R.S.(Biodiversity Heritage Library).

Mary continued to pursue paleontology while raising her children and doing charity work. She made specimen boxes and labels and repaired fossils. While William and Mary frequently collaborated, William did not approve of women working professionally in science. Even so, he was glad to benefit from Mary’s illustrations, editing skills, and scientific knowledge. Their son Frank wrote about his mother’s contributions to his father’s work, saying in part:

Not only was she a pious, amiable, and excellent helpmate to my father; but being naturally endowed with great mental powers, habits of perseverance and order, tempered by excellent judgment, she materially assisted her husband in his literary labours, and often gave to them a polish which added not a little to their merit.

— Frank T. Buckland (1858), Memoir in W. Buckland (1858) Geology and mineralogy considered with reference to natural theology, vol. 1, 3rd. ed.

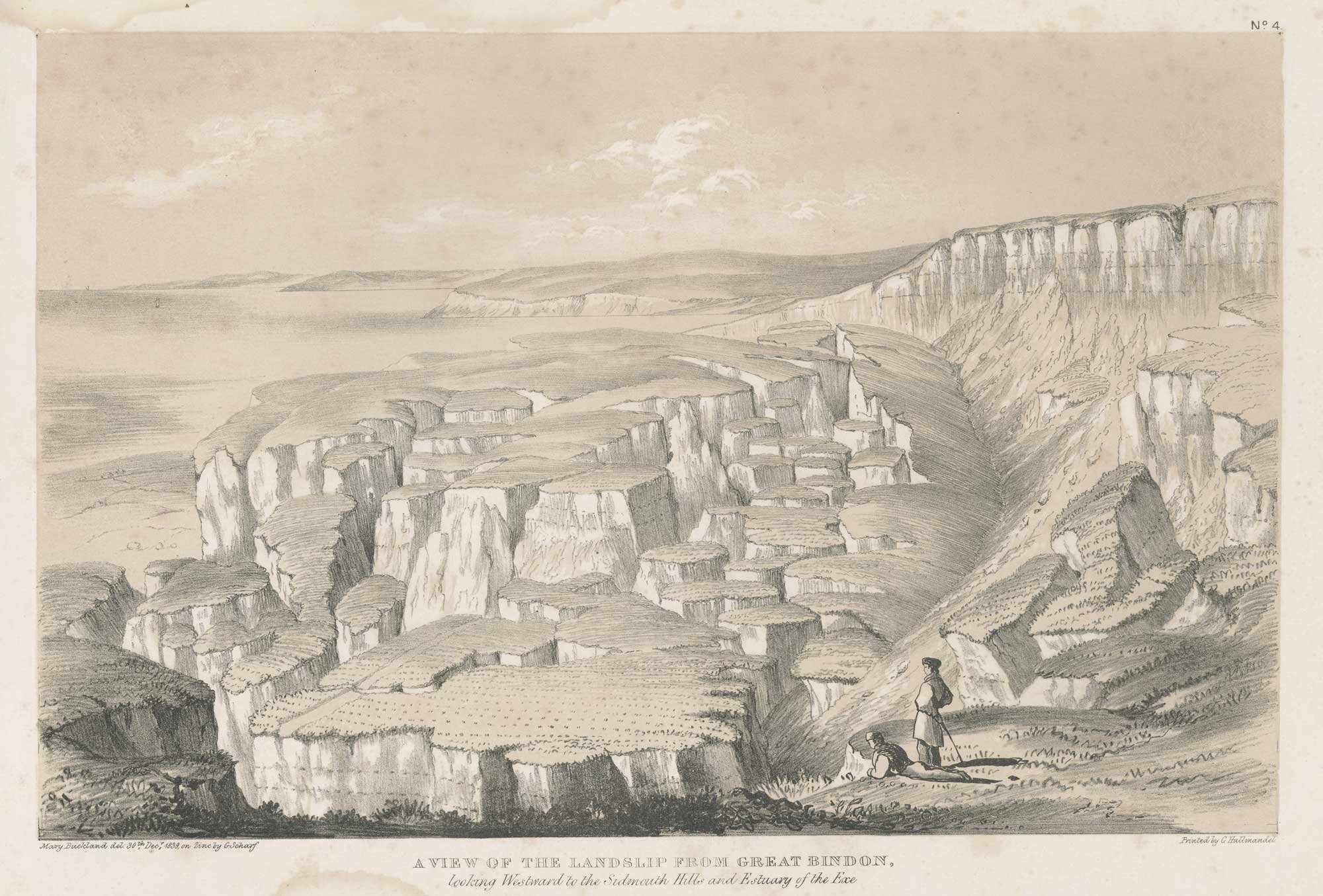

William’s colleagues knew that Mary contributed to his scholarship and improved his writing, but William rarely gave her credit. After their marriage, Mary was acknowledged for a few drawings in William’s contribution to the Bridgewater Treatises. According to Frank, she also took dictation from William while he composed the treatise, the two working for months, often through the night. She also did some signed drawings in an 1840 book about landslips by William Conybeare and William Dawson.

After William’s death in 1856, Mary moved to St. Leonard’s-on-Sea and studied marine bryozoans (coral-like animals that live in water) with her daughter Caroline. She died on November 30, 1857, and was buried beside her husband at Islip.

Selected works with illustrations by Mary Moreland Buckland

Buckland, W. 1822. Account of an assemblage of fossil teeth and bones of elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, bear, tiger, and hyaena, and sixteen other animals; discovered in a cave at Kirkdale, Yorkshire, in the year 1821. Philosophical Transactions 112: 171–236, plates 15–26. Link

Buckland, W. 1823. Reliquiae diluvianae or, observations on the organic remains contained in caves, fissures, and diluvial gravel and on other geological phenomena, attesting to the action of an universal deluge. John Murray, London. Link

Buckland, W. 1824. Notice on the Megalosaurus or great fossil lizard of Stonesfield. Transactions of the Geological Society, ser. 2, 1: 390–396, plates 40–44. Link

Buckland, W. 1841. Geology and mineralogy considered with reference to natural theology, vol. 2. The Bridgewater Treatises on the power, wisdom and goodness of God as manifested in the creation. Treatise 6. Lea & Blanchard, Philadelphia. Link

Buckland, W. 1858. Geology and mineralogy considered with reference to natural theology, vols. 1, 2. The Bridgewater Treatises on the power, wisdom and goodness of God as manifested in the creation. Treatise 6, F.T. Buckland, ed. George Routledge & Co., London. Link

Conybeare, W.D., and W. Dawson. 1840. Memoir and views of landslips on the coast of East Devon, & c. John Murray, London. Page images here: Link

Biographical references & further reading

Berta, A., and S. Turner. 2020. Rebels, scholars, explorers: Women in vertebrate paleontology. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bompas, G.C. 1886. Life of Frank Buckland, 11th ed. Smith, Elder, & Co., London. Link

Castano, F. no date. Mary Buckland: A fossiliferous life. Trowelblazers. Link

Costantino, G. 2015. The first described and validly named dinosaur: Megalosaurus. Biodiversity Heritage Library Blog, 15 October 2015. Link

Frith, U. 2011. Females, fossils and hyenas - part 1. The Royal Society: Blog, 7 February 2011. Link

Frith, U. 2011. Females, fossils and hyenas - part 2. The Royal Society: Blog, 11 February 2011. Link

Gordon, E.O. 1894. The life and correspondence of William Buckland, D.D., F.R.S. John Murray, Albemarle Street. Link

Kölbl-Ebert, M. 1997. Mary Buckland, née Morland 1797–1857. Earth Sciences History 16: 33–38.

Morgan, N. 2019. Distant thunder: Behind every good man . . . Geoscientist 29(6). Link

Torrens, H.S. 2008. Buckland [née Morland], Mary (1797–1857), geological artist and curator. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

Turner, S., C.V. Burek, and R.T. Moody. 2010. Forgotten women in an extinct saurian (man’s) world. In R.T.J. Moody, E. Buffetaut, D. Naish, and D.M. Martill, eds. Dinosaurs and other extinct saurians: A historical perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343: 111–153. Link