Julia Gardner

Julia Gardner

Julia Gardner

1882–1960

Julia Anna Gardner is best known for her research on the biostratigraphy and paleontology of the Atlantic and U.S. Gulf Coastal plains. There, she played a key role in the development of the oil industry. She is also known for her work on fossil mollusks.

“In these days when all Europe seems about to crash, even the memory of the color and the carved expanse of the Grand Cañon of the Colorado makes the terror of the present weeks seem more fugitive.”

- Julia Gardner (1940) “Notes on travel and life” (as quoted in Gries 2018)

Julia attended Bryn Mawr College when geologist Florence Bascom was on the faculty. In 1893, Florence had been the first woman to receive a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University. Florence was not allowed to formally enroll, however, in order to keep her presence off the books. She was hidden behind a screen during classes. Julia later followed Florence’s path to Johns Hopkins. Julia was the first woman to formally enroll as a student in the Department of Geology at Johns Hopkins, receiving her Ph.D. in 1911.

Julia was well traveled and adventurous. She was deeply concerned about World War I. In 1917, she went to France and served in the American Canteen Service and as an auxiliary nurse. She returned to the United States in 1920 and became one of a few women working as geologists at the United States Geological Survey (USGS), along with two friends from Bryn Mawr: petrologists Eleanora Bliss Knopf (1883–1974) and Anna I. Jonas Stose (1881–1974). The three would remain close for many years:

“In later years, Pick and Hammer shows would portray them with parodies of the Gilbert and Sullivan ditty: ‘Three little girls from school are we. . . .’ (they were all distinctly short of stature, Miss Bliss being the most petite), but all three held their own successfully by sheer brainpower and accomplishment. Each in her prime was acknowledged as an outstanding specialist in her own field. This was long before Women’s Lib and the downfall of the superstition that ‘geology is a man’s game.’”

— John Rodgers, Geological Society of America Memorial to Eleanora Bliss Knopf

In the period between World Wars, Julia learned to drive and did field work in the southeastern United States and Texas. She usually worked alone. She recalled her first solo trip to the field, when her car headlights went out and she had to navigate down a road in the Okeechobee Swamp in the dark:

“The road was getting narrow and sandy and on either side was the Okeechobee Swamp. There were no settlements and no passing cars. . . . I hesitated to turn on the car lights and thus black out the beauty of the scene around me. When at last I turned the switch, nothing happened. I had no lights. As in many other unpleasant situations, there was very little to be done about it. . . . The light sandy road could still be followed with frequent stalls at the bridges which were narrow and dark, some with and some without side railings. When the half moon rose, the sandy road caught the dim light. A big cat screamed off in the swamp and, far away, I could hear men shouting. I half hoped, half feared, they would come nearer.

After a long time, I saw, in the road ahead, a blur of light, which slowly disintegrated into the headlights of two parked cars and the lantern which came wavering down the road and was swung in my face. The man behind the lantern said ‘Oh, my God, it’s a woman.’ He was the driver of one of the two automobiles from some point in the Middle West. . . . I trailed them to Midway, at that time a filling station and cross roads store under a single roof. With my car parked in its shadow and my feet on the seat, I slept the rest of my first night in the field. My mileage that day was thirty-one. They told me the next morning that the shouts I had heard were those of men hunting some escaped convicts.”

— Julia Gardner (1940) “Notes on travel and life” (reprinted in Gries 2018)

During World War II, Julia was part of the Dungeon Gang in the USGS Military Geology Unit. She helped in the effort to pinpoint the launch site of Japanese balloon bombs (see below). After the war, she was temporarily based in Tokyo, Japan, working on geologic mapping for the National Resources Section, Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

Julia was a mentor and close colleague to many other women, including Winifred Goldring, Esther Applin, and Helen Plummer. She was given the Distinguished Service Medal, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s highest honor, when she retired from the USGS.

Echpora gardnerae

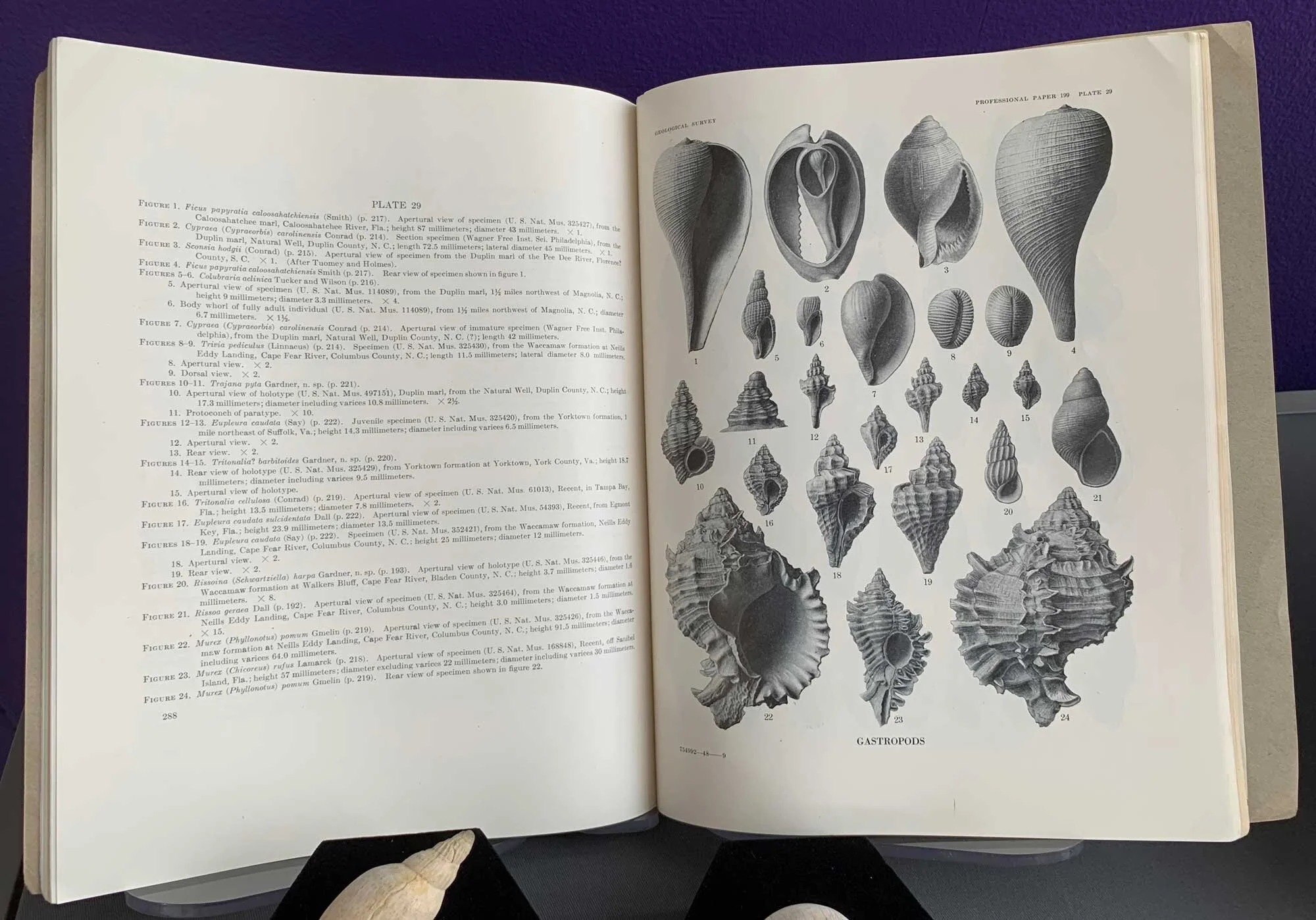

Does the shell below look a little familiar? It is part of the Paleontological Research Institution’s logo and has been associated with PRI since its founding in 1932 (learn more here). This species of snail is named Ecphora gardnerae in honor of Julia Gardner. The fossil shown is from the Miocene St. Marys Formation of St. Marys County, Maryland. Ecphora gardnerae gardnerae—yes, “gardnerae” is repeated because it is a subspecies name, or name below the rank of species—is the state fossil shell of Maryland.

Balloon Bombs

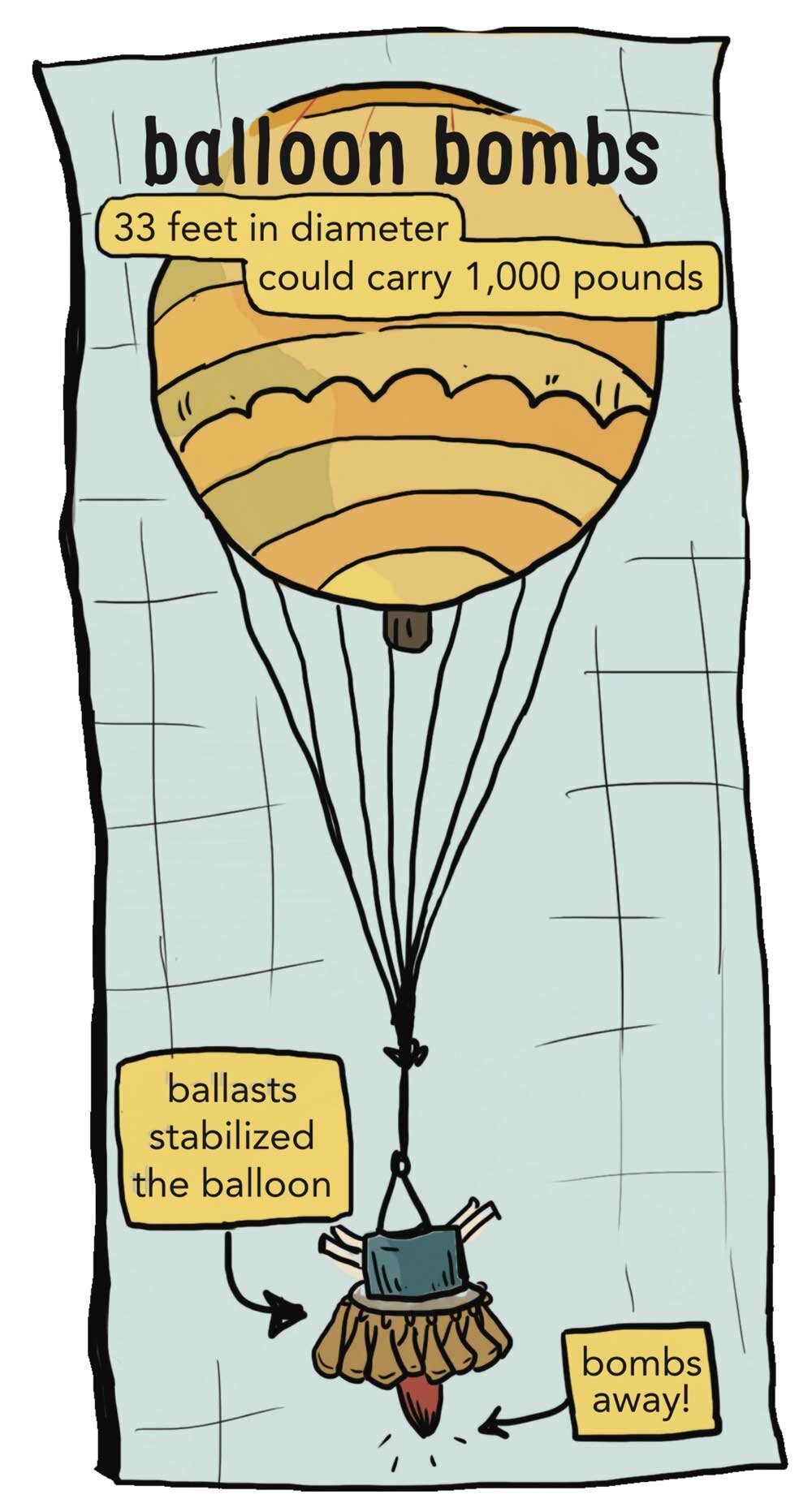

Illustration of a balloon bomb by Alana McGillis.

During World War II, Japan developed an unusual weapon: balloon bombs. A balloon bomb was a large balloon about 10 meters (33 feet) in diameter carrying several bombs and many sand-filled bags. The sandbags helped control the altitude of the balloon. Bags were dropped when the balloon descended too much. Once the sandbags were gone, the bombs would be released. By the time they reached North America, most balloon bombs had dropped all their sandbags, so few were recovered.

Over 9,000 balloon bombs were released from Japan in 1944 and 1945. They were carried across the Pacific via the jet stream, with a fraction reaching North America. Parts of bombs were found in the United States, Canada, and Mexico during the war. Only one bomb proved deadly, killing six people in Oregon. Remains of balloon bombs are still found sometimes, including as recently as 2014 in Canada.

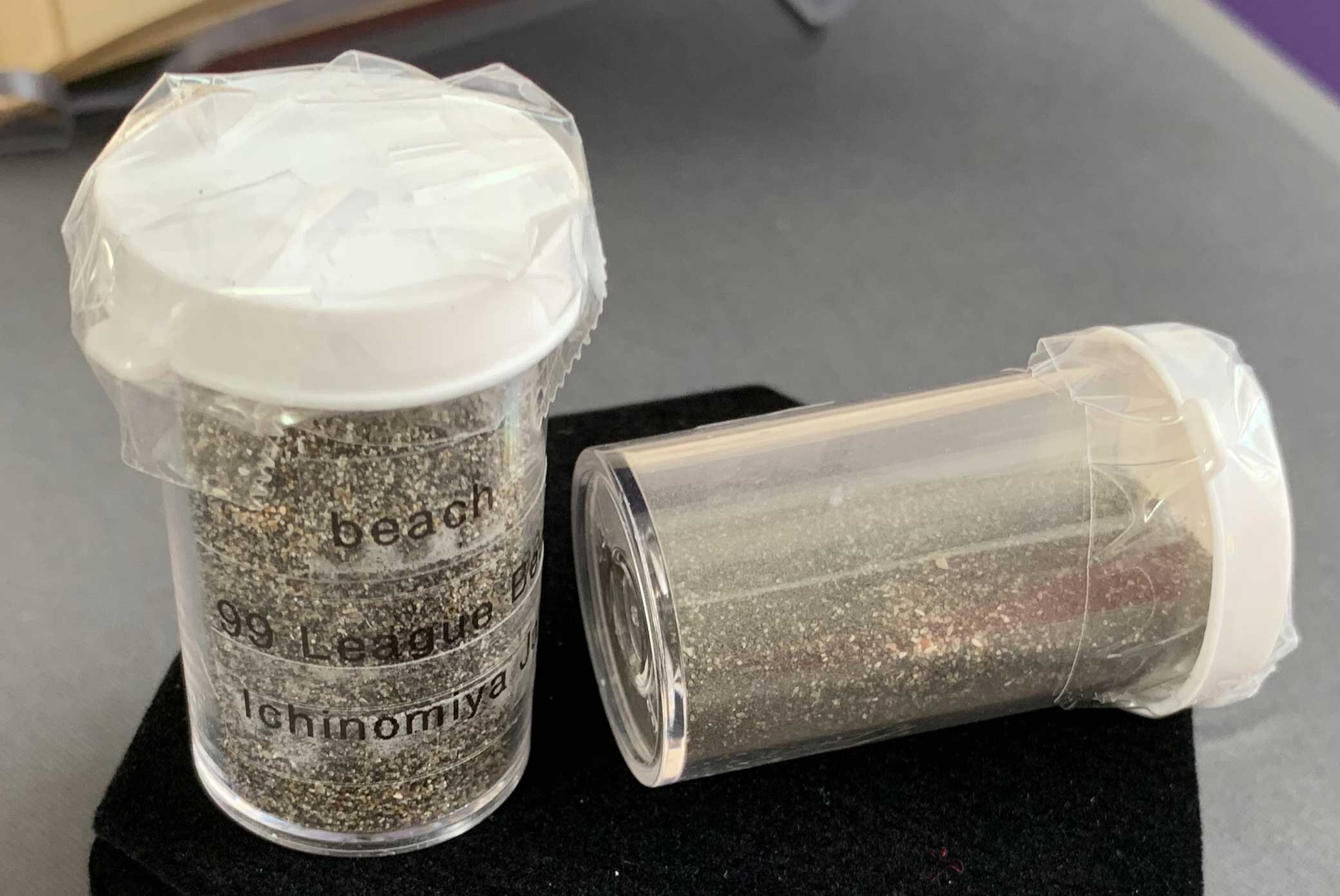

The U.S. War Department asked the USGS Military Geology Unit to figure out where the sand used in the balloon bombs came from. A team of geologists—including paleontologists Julia Gardner (mollusks), Kathryn Lohman (forams), and Kenneth Lohman (diatoms)—worked on the project. The paleontologists noted the types of fossils and modern organisms in the sand, as well as the lack of coral. That information, combined with an analysis of the sand itself, allowed the team to narrow the source of the sand to two beaches in Japan. Eventually, the military bombed two factories near one of the beaches. By then, however, the Japanese had given up on the balloon bomb project.

Two samples of beach sediment from Ichinomiya, Japan. This beach was the likely source for the sand used in the balloon bombs. Paleontological Research Institution.

Selected works by Julia Gardner

Gardner, J. 1927. The correlation of the marine Yegua of the type sections. Journal of Paleontology 1: 245–251. Link

Gardner, J. 1936. Additions to the molluscan fauna of the Alum Bluff Group of Florida. Geological Bulletin 14, 82 pgs. Stated Board of Conservation, Geological Department, Tallahassee, Florida. Link

Gardner, J. 1939. Recent collections of upper Eocene mollusca from Alabama and Mississippi. Journal of Paleontology 13: 340–343. Link

Gardner, J. 1941. Analysis of Midway fauna of western Gulf Province. AAPG Bulletin 25: 644–649. Link

Biographical references & further reading

Allmon, W.D. 2020. Ecphora: The snail shell of PRI. PRI blog, 27 January 2020. Link

Clary, R.M., and J.H. Wandersee. 2007. Great expectations: Florence Bascom (1842–1945) and the education of early US women geologists. In: C.V. Burek and B. Higgs, eds. The role of women in the history of geology. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 281: 125–135. Link

Considine, B. 2007. Julia Anna Gardner. Link

Edger, T. 2013. A paleontologist pens a few words for her alumnae magazine. Link

Gardner, J.A. 1940. Notes on travel and life. Johns Hopkins Alumni Magazine 28(2): 37–42. Reprinted in Gries, R. R. 2018. Anomalies—Pioneering women in petroleum geology: 1917–2017. Revised Edition. Steuben Press, Longmont, Colorado. Pp. 83–87.

Gries, R. R. 2018. Anomalies—Pioneering women in petroleum geology: 1917–2017. Revised Edition. Steuben Press, Longmont, Colorado.

Knisley, K. [no date] Florence Bascom: Groundbreaking geologist. Berkshire museum@home. Link

Ladd, H.S. 1962. Memorial to Julia Anna Gardner (1882–1960). Proceedings of the Geological Society of America, Annual Report for 1960, pp. 87–92. Link

Nelson, C.M., and M.E. Williams, 1986, Julia Gardner. Pp. , pp. 260–262 in B. Sicherman and C.H. Green, eds. Notable American women: A biographical dictionary: The modern Period. Harvard University Press.

Rodgers, J. Memorial to Eleanora Bliss Knopf 1883–1974. Link

Rossiter, M.W. 1982. Women scientists in America: Struggles and strategies to 1940. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

Sayre, A.N. 1961. Memorial: Julia Ann Gardner (1882–1960). AAPG Bulletin 45: 1418– 1421.

Shapiro, B., 1999/2000, Gardner, Julia Anna. American National Biography Online. Link

Stricker, B. 2017. Daring to dig : Adventures of women in American paleontology. PRI Special Publication No. 54. Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York.

Wilson, D. 1962. Julia Anna Gardner, 1882–1960. The Nautilus 75: 122–123. Link

Vincent, A. 2020. Reclaiming the memory of pioneer female geologists 1800–1929. Advances in Geosciences 53: 129–154. Link

Balloon bombs

Coen, R. 2010. “If one should come your way, shoot it down”: The Alaska Territorial Guard and the Japanese balloon bomb attack of World War II. Alaska History 25: 1–19.

Felton, Mark. Japanese Balloon Bombs by Mark Felton Productions. YouTube Video. Link

Klein, C. 2018. Attack of Japan’s killer WWII balloons, 70 years. Ago. History Stories. Link

Mikesh, R.C. 1973. Japan’s World War II balloon bomb attacks on North America. Smithsonian Annals of Flight, no. 9. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington. Link

McPhee, J. 1996. The gravel page. The New Yorker, January 29, pp. 52–60.

Powles, J. M. 2003. Silent destruction: Japanese balloon bombs. World War II 17: 64–69.

Rabbitt, M.C., and C.M. Nelson. 2015. Minerals, lands, and geology for the common defense and general welfare—vol. 4, 1939–1961. Reston, VA, USGS. Link

Rizzo, J. 2013. Japan's secret WWII weapon: Balloon bombs. National Geographic. Link

Rogers, J. no date. How geologists unraveled the mystery of Japanese vengeance balloon bombs in World War II. Link

Tewkesbury, D.A. 2008. Japan’s balloon bomb attacks on North America - a GIS exercise for forensic geology. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs 40(6): 490. Link

Weeks, L. 2015. Beware of Japanese balloon bombs. National Public Radio History Department, January 20. Link