Mary Anning

Mary Anning

Mary Anning

1799–1847

No discussion of women in paleontology is complete without mentioning the most famous early trailblazer, Mary Anning. Mary was a British fossil collector from Lyme Regis, England. She has been called “the greatest fossilist the world ever knew.”

". . . according to her account these men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal by publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages."

– Anna Maria Pinney writing about her friend Mary Anning (as quoted in Lang 1954)

Mary learned fossil collecting from her father, Richard. He was cabinetmaker who made extra money from collecting and selling fossils to tourists who came to Lyme Regis. These fossils eroded out of the Jurassic seaside cliffs near the town. When Mary’s father died unexpectedly in 1810, 11-year-old Mary, her older brother Joseph, and their mother Mary (“Molly”) took on the work of finding and selling fossils. Without this income and religious charity, the Annings would have starved.

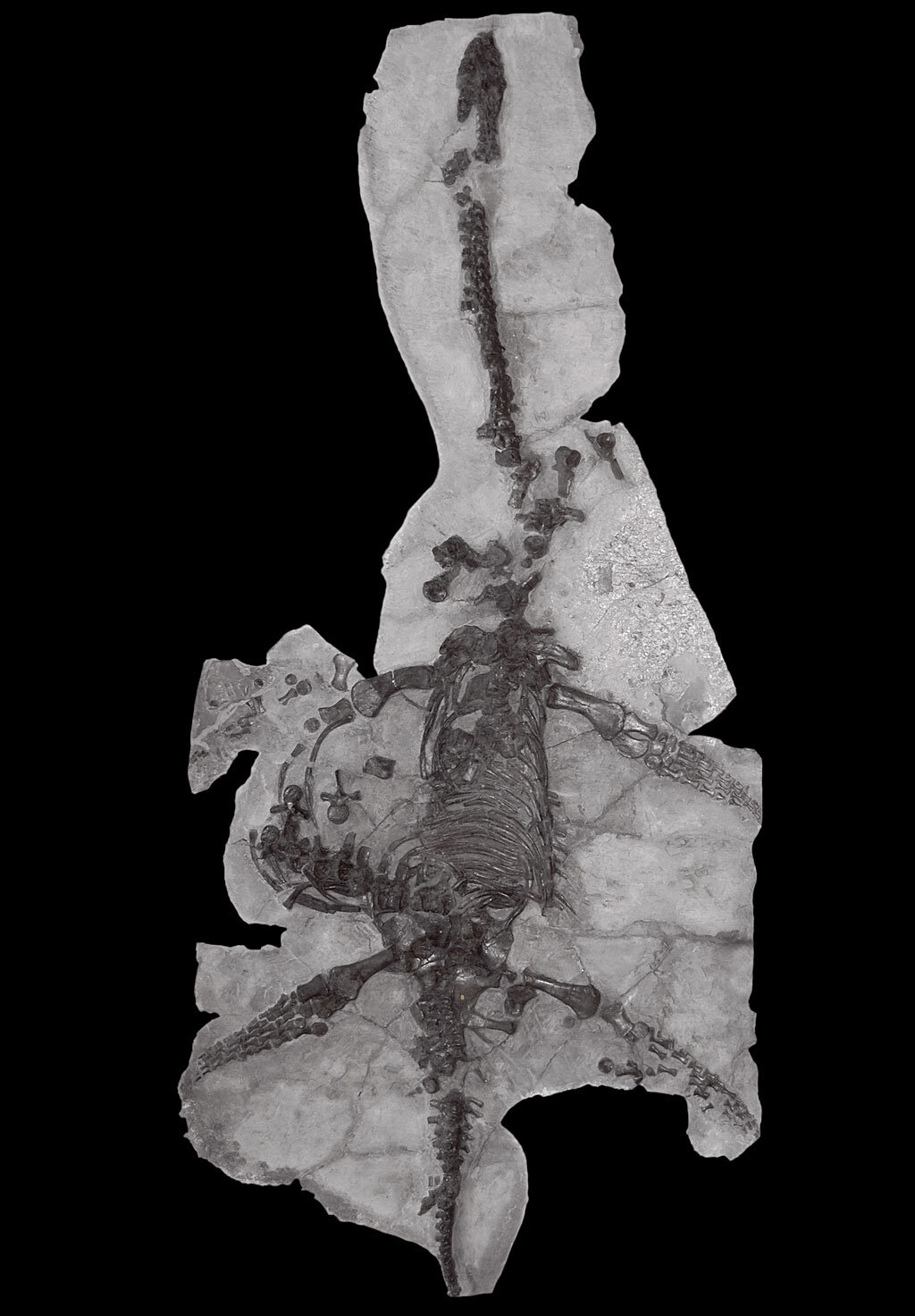

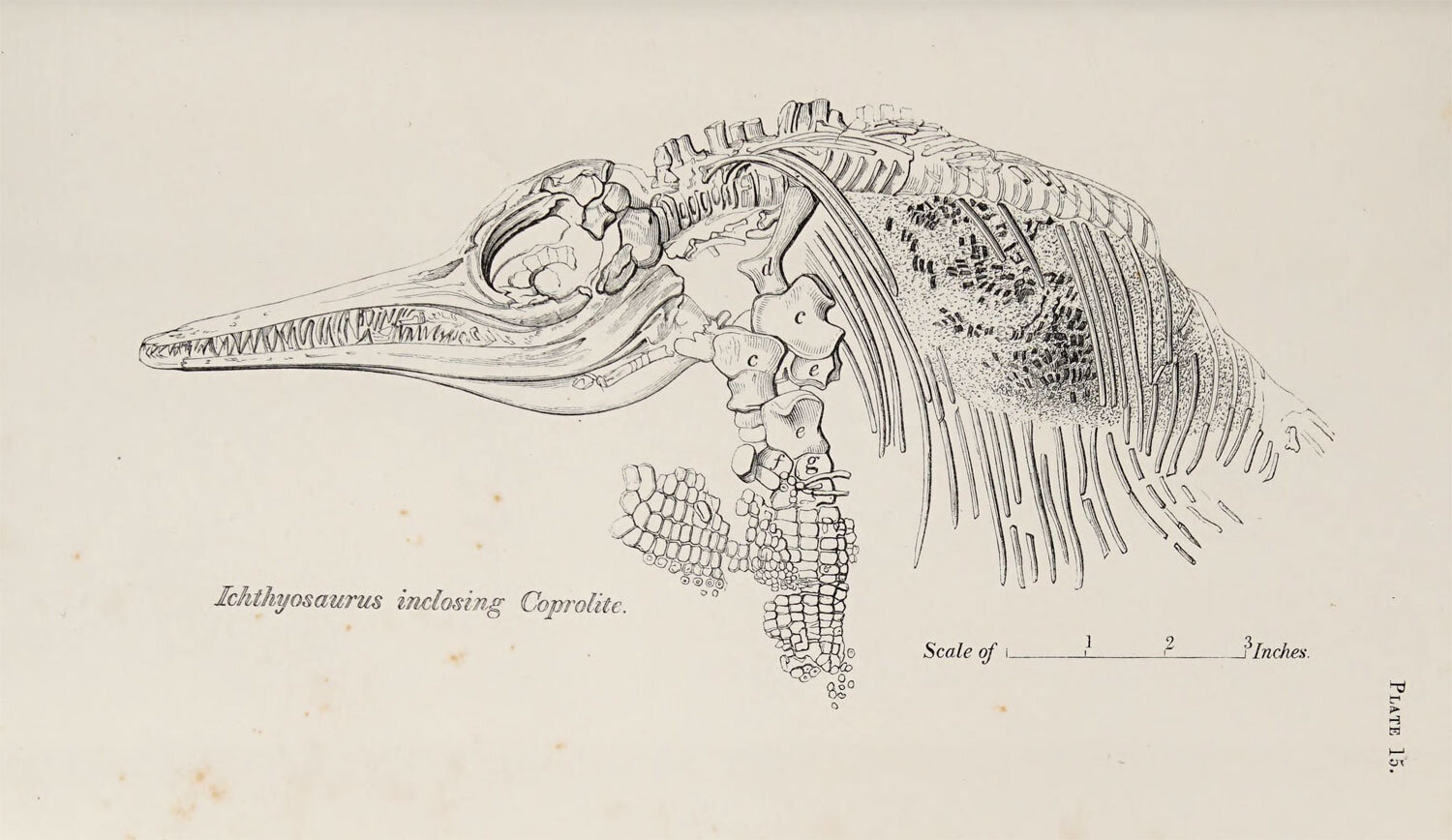

Mary and Joseph made an incredible find when Mary was just 12 years old. They uncovered an ichthyosaur, a swimming, dolphin-like reptile with large eyes. In 1823, when Mary around 24 years old, she discovered the skeleton of a plesiosaur, a long-necked marine reptile with four flippers. The plesiosaur skeleton was important because it was almost complete. These specimens were sold, and Mary was given no credit when they were scientifically described.

Skull of Ichthyosaurus platyodon discovered by Mary's brother Joseph in 1811. Mary discovered more of the skeleton in 1812 and also excavated the fossil. Source: Drawing by W. Clift in Home (1814) reprinted from Philosophical Transactions (Wellcome Collection).

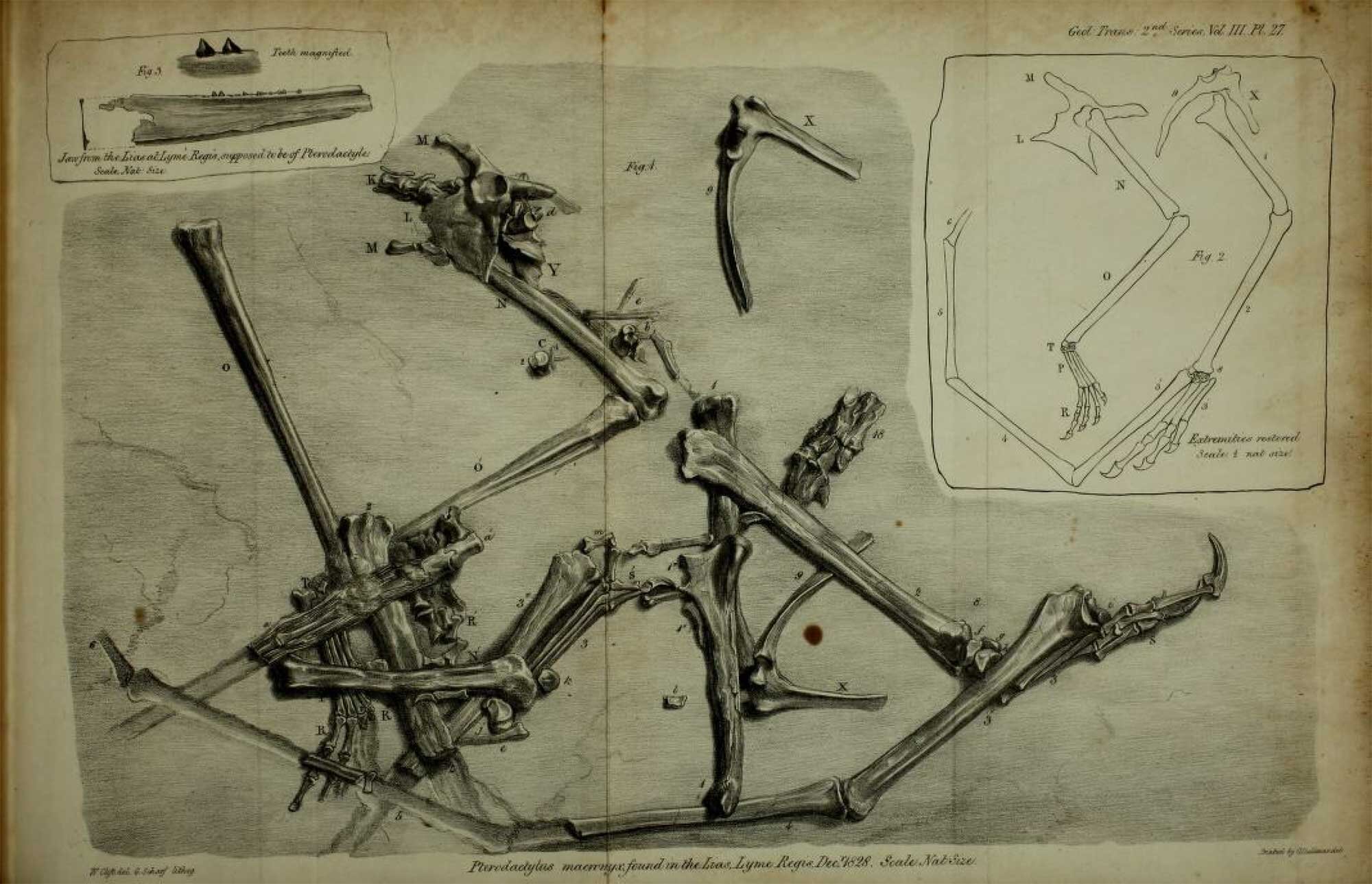

In 1828, Mary discovered the first British pterosaur, a type of winged, flying reptile. William Buckland described the new animal. In his paper, William gave credit to Mary for discovering the pterosaur and other fossils:

In the same blue lias formation at Lyme Regis, in which so many specimens of Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus have been discovered by Miss Mary Anning, she has recently found the skeleton of an unknown species of that most rare and curious of all reptiles, the Pterodactyle . . .”

This illustration shows a pterosaur (Dimorphodon macronyx), an ancient flying reptile found by Mary in 1828. It was the first pterosaur found in England. William Buckland described it in 1829, and this illustration appeared in 1835. Source: Drawing by W. Clift (Biodiversity Heritage Library).

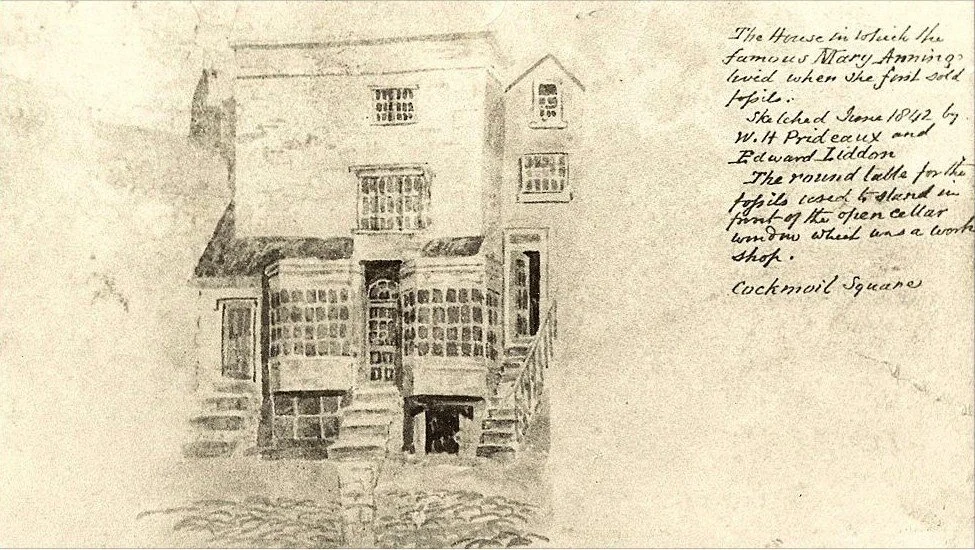

Mary eventually made enough money to buy a house with a storefront to sell her finds. She spent her days hunting fossils along dangerous beachside cliffs. In 1833, she was nearly crushed by a rockfall that killed Tray, her beloved dog. A newspaper, the Bristol Mirror, provided a description of her fossil-hunting routine:

This persevering female has for years gone daily in search of fossil remains of importance at every tide, for many miles under the hanging cliffs at Lyme, whose fallen masses are her immediate object, as they alone contain these valuable relics of a former world, which must be snatched at the moment of their fall, at the continual risk of being crushed by the half suspended fragments they leave behind, or be left to be destroyed by the returning tide: — to her exertions we owe nearly all the fine specimens of Ichthyosauri of the great collections; and, to shew that it is one which rewards industry a single specimen of her’s . . . was lately sold to the College of Surgeons for the sum of One Hundred Pounds.” [100 pounds in 1823 was nearly 12,000 pounds in 2020, or over $16,000.]

— George Cumberland (January 1823) in the Bristol Mirror (as quoted by Torrens 1995)

Drawing of Mary's fossil shop, 1842, by W.H. Prideaux and E. Liddon. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In 1830, Mary found another amazing specimen. This specimen, later called Plesiosaurus macrocephalus, fetched a high price: 200 guineas. In 2020, the equivalent price would have been more than 24,000 British pounds ($33,000).

Once Mary had established her reputation, collectors traveled long distances to buy her fossils. Visitors to her shop called her the “geological Lioness” and “Princess of palaeontology.” When the King of Saxony stopped at her shop, she told his physician:

“I am well known through the whole of Europe.”

— Mary Anning to Dr. C.G. Carius in 1844 (as quoted in Carius, 1846)

Despite class divisions, Mary built friendships with other scientists. These friends included Mary and William Buckland, fossil collector Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Birch, and Etheldred Benett, often considered to be the first female geologist. Mary taught herself anatomy from borrowed books and learned to prepare and create scientific illustrations.

Mary died of cancer at age 47. She became the first woman memorialized by the Geological Society of London, although, as a woman, she had not been allowed to join.

Many fossils have been named in Mary’s honor, including the plesiosaur Anningasaura. The former location of her home is now the site of the Lyme Regis Museum. The museum was built by a descendant of the Philpot sisters, who were Mary’s friends and fellow fossil collectors. The area where she collected fossils is now part of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site.

Fossils named after Mary

Selected works by Mary Anning

Anning, M. 1839. Note on the supposed frontal spine in the genus Hybodus. Magazine of Natural History 36: 605.

Selected descriptive works about Mary Anning’s discoveries

Buckland, W. 1829. On the discovery of a new species of Pterodactyle in the Lias of Lyme Regis. Transactions of the Geologica Society of London S2–3: 217–222. Link

Buckland, W. 1829. On the discovery of coprolites, or fossil faeces, in the Lias at Lyme Regis, and in other formations. Transactions of the Geological Society of London S2–3: 223–236. Link

Buckland, W. 1858. Geology and mineralogy considered with reference to natural theology, vol. 2. The Bridgewater Treatises on the power, wisdom and goodness of God as manifested in the creation. Treatise 6, F.T. Buckland, ed. George Routledge & Co., London. Link

Home, E. 1814. Some account of the fossil remains of an animal more nearly allied to fishes than any of the other classes of animals. From the Philosophical Transactions. W. Bulmer and Co., London. 6 pp., 3 plates. Link

Owen, R. 1840. A description of a specimen of the Plesiosaurus macrocephalus, Conybeare, in the collection of Viscount Cole, M.P., D.C.L., F.G.S., & c. Transactions of the Geological Society series 2, vol. 5: 515–535. Link

Vincent, P., and P. Taquet. 2010. A plesiosaur specimen from the Lias of Lyme Regis: the second ever discovered plesiosaur by Mary Anning. Geodiversitas 32: 377–390.

Other works about Mary Anning’s discoveries

De la Beche, H. 1830. Duria Antiquior. (This painting is based on Mary Anning’s fossil finds and was used to raise money for her support) Link

Other scientific references

Andrews, C.W. 1896. On the structure of the plesiosaurian skull. The Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 52: 246–253. Link

Vincent, P., and R.B.J. Benson. 2012. Anningasaura, a basal plesiosaurian (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Lower Jurassic of Lyme Regis, United Kingdom. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32: 1049–1063. Link

Biographical references & further reading

Bates, M. 2011. The legacy of Mary Anning, lifelong fossil hunter. AAAS, 18 October 2011. Link

Berta, A., and S. Turner. 2020. Rebels, scholars, explorers: Women in vertebrate paleontology. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Birch, S.P. no date. Mary Anning: Happy birthday Mary Anning! Trowelblazers. Link

Carius, C.G. 1846. The King of Saxony’s journey through England and Scotland in the year 1844. Chapman and Hall, London. Link

Clary, R.M., and J.H. Wandersee. 2006. Mary Anning. She’s more than “Seller of Sea Shells at the Seashore.” The American Biology Teacher 68: 153–157. Link

Currie, A. 2018. Mary Anning: how a poor, Victorian woman became one of the world’s greatest palaeontologists. The Conversation, 2 November 2018. Link

Davis 2009. Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th century pioneer of British palaeontology. Headwaters 26: 96–126. Link

Dorset County Council. 2000. Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List. Link

Elder, E.S. 1982. Women in early geology. Journal of Geological Education 30: 287–293. Link

Emling, S. 2009. The fossil hunter: Dinosaurs, evolution, and the woman whose discoveries changed the world. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Forges, N. no date. Mary Anning and Dorset’s Jurassic Coast: History set in stone. Britain: The Official Magazine. Link

Goodhue, T.W. 2004. Fossil hunter: The life and times of Mary Anning (1799–1847). Academica Press.

Goodhue, T.W. 2019. Mary Anning’s Commonplace Book. Lyme Regis Museum. Link

Lang, W.D. 1954. Mary Anning and Anna Maria Pinney. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 76: 146–152.

Lyme Regis Museum. No date. About us. Link

Martill, D.M. 2010. The early history of pterosaur discovery in Great Britain. In R.T.J. Moody, E. Bufetaut, D. Naish, and D.M. Martill, eds. Dinosaurs and other extinct saurians: A historical perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343: 287–311. Link

O’Connor, M. 2019. Women in science – Mary Anning. The Oxford Scientist. Link

Oxford University Museum of Natural History. No date. Mary Anning’s ichthyosaur. Link

Pierce, P. 2006. Jurassic Mary. Mary Anning and the primeval monsters. The History Press, Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK.

Torrens, H. 1995. Mary Anning (1799–1847) of Lyme; “The greatest fossilist the world ever knew.” The British Journal for the History of Science 25: 257–284. Link

Torrens, H., 2008, Anning, Mary. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Link

Turner, S., C.V. Burek, and R.T. Moody. 2010. Forgotten women in an extinct saurian (man’s) world. In R.T.J. Moody, E. Buffetaut, D. Naish, and D.M. Martill, eds. Dinosaurs and other extinct saurians: A historical perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343: 111–153. Link